"there are immaturities, but there are immensities" - Bright Star (dir. Jane Campion)>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "the fear of being wrong can keep you from being anything at all" - Nayland Blake >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "It may be foolish to be foolish, but, somehow, even more so, to not be" - Airport Through The Trees

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Friday, May 22, 2020

Trunk - Now We Are Ten compilation review + profile of Jonny Trunk

Various, Now We Are Ten

The Observer Review, July 14 2007

by Simon Reynolds

For more than a decade, 38-year-old Brit Jonny Trunk has trawled charity shops, bargain basements and jumble sales, sifting the dreck for bygone oddities and queer delectables. Chasing down obscure objects of collector desire or stumbling serendipitously on unknown treasures, Trunk has then tracked down the music's elderly creators (invariably languishing in penury) and prised the right-to-reissue from their bony mitts.

Jonny Boy specialises in genres of marginal reputation: never-before-available soundtracks from horror movies such as The Wicker Man, incidental music from kids' TV programmes such as The Tomorrow People, fey folk-pop, library music. His sensibility lies at the exact intersection of Stereolab, Saint Etienne and el Records, but if that sounds too tasteful, you've got to factor in Trunk's penchant for period pornography. Not only did he reissue Mary Millington's spoken-word records, he made a brand new one, Dirty Fan Male, which involved an actor friend, Wisbey, reading out lewd letters sent to Trunk's sister, a soft-porn starlet, and her colleagues. One appears as a hidden track at the end of this excellent compilation: 'I think that my tongue would have to be surgically removed from your mouth-watering botty ...'

There's a serious core behind all this dotty whimsy: Trunk's most crucial excavations have been works by maverick composers such as Basil Kirchin, Delia Derbyshire and Desmond Leslie, pioneers of a peculiarly English form of musique concrete and analogue electronica that often sounds like it was cobbled together in a garden shed. The late Kirchin features with the uncharacteristically wispy femme-pop of 'I Start Counting', while the even later Derbyshire briefly appears with a 37-second synth-interlude. But overall, Now We Are Ten downplays electronics in favour of acoustic instrument-based soundtracks and light-on-the-ear Brit-jazz, resulting in an unusually coherent compilation.

Highlights include the pastel-toned poignancy of 'Dark World' and 'Nature Waltz' by Sven Libaek, the fragrant waft 'n' flutter of Paul Lewis's 'Waiting For Nina' and Trunk's own 'O Zeus' (meta-library music woven out of samples from that incidental music genre typically churned out of Soho studios by moonlighting composers). If the cloying flute of John Cameron's theme from Kes requires the sour bleakness of the movie to offset its sweetness, Vernon Elliott's Clangers music has a stand-alone magic.

Rescuing such figures as Elliott and Kirchin from history's rubbish tip is a valuable feat of cultural archaeology, and Now We Are Ten is the sweet sound of someone giving their own trumpet a well-deserved blow. Fnarr fnarr.

Trunk Records

for an art magazine whose name I cannot remember, 2007

by Simon Reynolds

Cheesy sleaze and sepia-toned melancholy seem unlikely bedfellows at first glance. But in his 1935 travel book Journey Without Maps, Graham Greene put his finger on or near the place where musty and lust meet. He wrote about how "seediness has a very deep appeal ... It seems to satisfy, temporarily, the sense of nostalgia for something lost; it seems to represent a stage further back"

With their aura of wistful reverie and faded decay, the sounds exhumed by Trunk offer a portal into this nation’s cultural unconscious.

see also this very interesting recent chat with Mr Trunk on the story of how he tracked down The Wicker Man soundtrack

The Observer Review, July 14 2007

by Simon Reynolds

For more than a decade, 38-year-old Brit Jonny Trunk has trawled charity shops, bargain basements and jumble sales, sifting the dreck for bygone oddities and queer delectables. Chasing down obscure objects of collector desire or stumbling serendipitously on unknown treasures, Trunk has then tracked down the music's elderly creators (invariably languishing in penury) and prised the right-to-reissue from their bony mitts.

Jonny Boy specialises in genres of marginal reputation: never-before-available soundtracks from horror movies such as The Wicker Man, incidental music from kids' TV programmes such as The Tomorrow People, fey folk-pop, library music. His sensibility lies at the exact intersection of Stereolab, Saint Etienne and el Records, but if that sounds too tasteful, you've got to factor in Trunk's penchant for period pornography. Not only did he reissue Mary Millington's spoken-word records, he made a brand new one, Dirty Fan Male, which involved an actor friend, Wisbey, reading out lewd letters sent to Trunk's sister, a soft-porn starlet, and her colleagues. One appears as a hidden track at the end of this excellent compilation: 'I think that my tongue would have to be surgically removed from your mouth-watering botty ...'

There's a serious core behind all this dotty whimsy: Trunk's most crucial excavations have been works by maverick composers such as Basil Kirchin, Delia Derbyshire and Desmond Leslie, pioneers of a peculiarly English form of musique concrete and analogue electronica that often sounds like it was cobbled together in a garden shed. The late Kirchin features with the uncharacteristically wispy femme-pop of 'I Start Counting', while the even later Derbyshire briefly appears with a 37-second synth-interlude. But overall, Now We Are Ten downplays electronics in favour of acoustic instrument-based soundtracks and light-on-the-ear Brit-jazz, resulting in an unusually coherent compilation.

Highlights include the pastel-toned poignancy of 'Dark World' and 'Nature Waltz' by Sven Libaek, the fragrant waft 'n' flutter of Paul Lewis's 'Waiting For Nina' and Trunk's own 'O Zeus' (meta-library music woven out of samples from that incidental music genre typically churned out of Soho studios by moonlighting composers). If the cloying flute of John Cameron's theme from Kes requires the sour bleakness of the movie to offset its sweetness, Vernon Elliott's Clangers music has a stand-alone magic.

Rescuing such figures as Elliott and Kirchin from history's rubbish tip is a valuable feat of cultural archaeology, and Now We Are Ten is the sweet sound of someone giving their own trumpet a well-deserved blow. Fnarr fnarr.

Trunk Records

for an art magazine whose name I cannot remember, 2007

by Simon Reynolds

The record business may not have much of a future, but it’s

got one hell of a past: sales are plummeting, sending the industry into a state

of panicked paralysis, but one of the few growth zones is ‘salvage’. That’s

writer John Carney’s term for the modus operandi of labels like LTM, Soul Jazz

and Anthology, who comb the back catalogues of defunct record companies in

search of out-of-print nuggets. Then there’s Trunk, currently celebrating a

decade of quirky excavations with the compilation Now We Are Ten.

The label is not just one man’s vision, it’s one man (38-year-old

Jonny Trunk, nee Jonathan Benton-Hughes) finding an ingenious way of making his

unhealthy obsessions-- specifically, the compulsion to dig in the dusty crates

for vintage vinyl--work for him. “Records have been good to me,” he notes wryly

but with a note of genuine gratitude. In addition to running his much-admired

label, he also writes about music and deejays frequently, in clubs and on his

regular show for Resonance FM.

In recent years, the word “curate” has become a slightly

annoying buzzword in the hipster music scene, with people pompously describing

functions hitherto designated more prosaically as “pulling together a compilation,” “running a record label,” or “booking bands

for a festival” in terms of curating. Still, if anybody deserves to be thought

of in these terms, it’s Trunk. Along with likeminded operatives such as Saint

Etienne, Broadcast, and The Focus Group, Trunk explores music’s archives in

search of lost futures and alternate presents. As much a historian as an

entrepreneur, he remaps the past, finding the paths-not-taken and the peculiar

but fertile backwaters adjacent to pop’s official narrative.

Trunk got into the creative curatorship game with its very

first release, The Super Sounds of Bosworth (1996), which was also the world’s

first compilation of library music. Bosworth is the company that pioneered the

library concept: incidental music for use in radio, cinema advertisements, industrial

films, and other non-glamorous contexts, sold by subscription not in shops, and

issued in institutional-looking sleeves with helpful track descriptions (

‘neutral underscore’, ‘pathetic, grotesque’). By the early 1990s, library

records from the Sixties and Seventies had become highly prized by hip hop

producers for their sample-ready

cornucopia of crisply-recorded and session musician-played beats, fanfares, and

refrains.

In addition to lushly orchestrated soundtrack-style themes

and hot snippets of funk and jazz, the library companies generated plenty of

wacked-out experimental sounds, often using analogue synthesizers. That’s what

snagged Trunk’s attention. As a child, the first melody he ever sang was the

Doctor Who theme, whose electronic rendition by Delia Derbyshire of the BBC

Radiophonic Workshop sent shudders of anticipatory fear through millions of

kids’ bodies every week. Later, as a

teenager, Trunk became obsessed with the weird electronica “played on Open

University programs, like when there was a sequence about microbes”. But he could never find out who made it. Then

“someone played me a Bosworth album and I thought, ‘that’s it, the Open

University sound!”. Spotting the company’s address on the back of the record,

he “just walked around the corner” to their Central London

office and “knocked on the door”, finding inside a “Hammer House of Horror

scene” of decades-old dust and teetering piles of sheet music.

The name Trunk actually comes from friends teasing him about

being “nosy”. “There’s a part of me that wants to be a detective. I like

digging about.” His sleuth work tracked down maverick composers like Basil Kirchin and Desmond Leslie. The latter’s Music Of The

Future (1955 – ’59), homespun musique concrete recorded in the late 1950s, is

one of the label’s great discoveries. An ex-Spitfire pilot and UFO expert,

Leslie was a non-musician who fancied sparring with Pierres Schaeffer and

Henry. “A member of the landed gentry,” says Trunk, “he could afford to throw

rotating fans and buckets of sand into pianos”.

Another recently reissued gem is the library album made by Delia Derbyshire (moonlighting from her Beeb dayjob under the alias Russe) and later used to soundtrack the children’s TV science fiction series The Tomorrow People (1973). The library obsession culminated with an attractive compendium of library sleeves Trunk pulled together for the design book publisher Fuel. Ranging from stark modernist grids to surreal photocollages, from kitschadelic Op Art to bizarrely clumsy drawings that exert a macabre compulsion akin to outsider art, the artwork collected in The Music Library (2005) show how library covers could be as inadvertently avant-garde as the music it packaged. Which isn’t so surprising, given that both were produced in factory conditions where utilitarian practicality and experimental impulses coexisted on a tight budget.

Another recently reissued gem is the library album made by Delia Derbyshire (moonlighting from her Beeb dayjob under the alias Russe) and later used to soundtrack the children’s TV science fiction series The Tomorrow People (1973). The library obsession culminated with an attractive compendium of library sleeves Trunk pulled together for the design book publisher Fuel. Ranging from stark modernist grids to surreal photocollages, from kitschadelic Op Art to bizarrely clumsy drawings that exert a macabre compulsion akin to outsider art, the artwork collected in The Music Library (2005) show how library covers could be as inadvertently avant-garde as the music it packaged. Which isn’t so surprising, given that both were produced in factory conditions where utilitarian practicality and experimental impulses coexisted on a tight budget.

On Trunk’s website there’s the slogan: ‘music, sex, and

nostalgia’. For as long as he can remember, Trunk has been susceptible to a

bittersweet attraction to bygone things: while his friends followed the latest pop fashions, as a

child he was into “Henry Mancini’s The Party soundtrack… I don’t feel the new market as much as the

old one. I’m drawn to old things.”

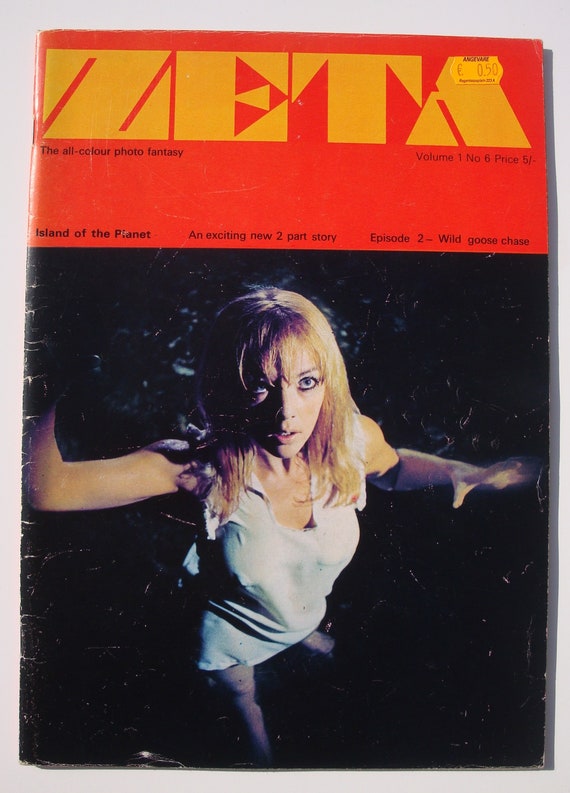

As for sex, that comes into it through his interest in vintage porn, which he claims is all about the period aesthetics rather than any prurient use-value. “You can’t beat a goodMayfair ”, Trunk

chuckles, before explaining that true connoisseurs hunt for late 1960s

periodical Zeta, with its stylish, cutting-edge photography (women in

scrapyards).

As with record collector culture, there are fashions on the vintage skin mag scene: “1980s rude mags, that’s the new hot zone -- all DayGlo knickers and shoulder pads.” Trunk put out Flexi Sex (2003), a collection of the ultra-lewd spoken word flexi-singles porn mags once stuck between their soon-to-be-stuck-together pages. Porn informed one of the label’s few non-reissue releases, Dirty Fan Male (2004), which involved an actor known as Wisbey reading out the filthy fan letters sent to British softcore pornstars, in an assortment of comedic voices. The CD gradually became a cult item, inspiring Trunk to turn it into a stage show, which played at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2004 and won the Guardian’s Best Concept award.

As for sex, that comes into it through his interest in vintage porn, which he claims is all about the period aesthetics rather than any prurient use-value. “You can’t beat a good

As with record collector culture, there are fashions on the vintage skin mag scene: “1980s rude mags, that’s the new hot zone -- all DayGlo knickers and shoulder pads.” Trunk put out Flexi Sex (2003), a collection of the ultra-lewd spoken word flexi-singles porn mags once stuck between their soon-to-be-stuck-together pages. Porn informed one of the label’s few non-reissue releases, Dirty Fan Male (2004), which involved an actor known as Wisbey reading out the filthy fan letters sent to British softcore pornstars, in an assortment of comedic voices. The CD gradually became a cult item, inspiring Trunk to turn it into a stage show, which played at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2004 and won the Guardian’s Best Concept award.

To ‘music, sex, nostalgia’, three other Trunk keywords could

be added.

Humour: a good-natured whimsy pervades the whole project.

Britishness: nearly everything on the label was made in the UK and there’s an affectionate fascination for all aspects of this country’s post-War popular culture (the label’s website is packed with Anglo curios Trunk has stumbled upon, from an album by Stanley Unwin, the comedian who spoke in an invented gobbledygook language, to a record by the show jumper Harvey Smith).

Keyword #3 is “melancholy”: Now We Are Ten teems with softly sad film music by composers like John Cameron and Sven Libaek.

Humour: a good-natured whimsy pervades the whole project.

Britishness: nearly everything on the label was made in the UK and there’s an affectionate fascination for all aspects of this country’s post-War popular culture (the label’s website is packed with Anglo curios Trunk has stumbled upon, from an album by Stanley Unwin, the comedian who spoke in an invented gobbledygook language, to a record by the show jumper Harvey Smith).

Keyword #3 is “melancholy”: Now We Are Ten teems with softly sad film music by composers like John Cameron and Sven Libaek.

Cheesy sleaze and sepia-toned melancholy seem unlikely bedfellows at first glance. But in his 1935 travel book Journey Without Maps, Graham Greene put his finger on or near the place where musty and lust meet. He wrote about how "seediness has a very deep appeal ... It seems to satisfy, temporarily, the sense of nostalgia for something lost; it seems to represent a stage further back"

With their aura of wistful reverie and faded decay, the sounds exhumed by Trunk offer a portal into this nation’s cultural unconscious.

see also this very interesting recent chat with Mr Trunk on the story of how he tracked down The Wicker Man soundtrack

Thursday, May 21, 2020

Tuesday, May 12, 2020

Thursday, May 7, 2020

Monday, May 4, 2020

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)