"there are immaturities, but there are immensities" - Bright Star (dir. Jane Campion)>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "the fear of being wrong can keep you from being anything at all" - Nayland Blake >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "It may be foolish to be foolish, but, somehow, even more so, to not be" - Airport Through The Trees

Wednesday, December 6, 2023

Sunday, November 12, 2023

Ibiza-ification of pop

The Ibiza-ification of pop

Guardian blog, 2011

by Simon Reynolds

The other

day we were driving in the car, listening to one of Los Angeles's Top 40 stations, and I turned to my wife and

asked, "How come everything on

the radio sounds like a peak-hour tune from Ibiza?"

All these

smash hits have the AutoTuned big-chorus tune bolted on top. But underneath,

the riffs and vamps, the pulses and pounding beats, the glistening synthetic

textures and the overall banging boshing feel: it's like it's been beamed

straight in from Gatecrasher or The Love Parade circa 1999.

This week

The Quietus published a piece that pinpoints a particularly bludgeoning and tyrannical aspect of the now-pop,

what writer Daniel Barrow calls "the Soar": the wooshing,

upwards-ascending, hands-in-the-air chorus, which has been divorced from its

original context (Nineties underground dance-and-drug culture) and repurposed

as the trigger for a kind of release-without-release.

Barrow's

references to steroids ("the steroided architecture of these tracks",

etc) captures the unsettling "stacked" quality of these recordings.

Like the images you find in bodybuilding magazines, the now-pop can often be at

once grotesque and mesmerising.

Strangely

Barrow makes no mention of the tune that seems like the now-pop's defining

anthem and blueprint, a song that is still omnipresent many months after it

first hit big: "Dynamite" by Taio Cruz. His name, with its odd

unplaceable quality (it sounds like some kind of Asian-Hispanic hybrid) suits

the Esperanto-like qualities of the

now-pop. Although often described by

hostile critics as Eurohouse, it is simply and purely international,

post-geographical, panglobal.

I started out loathing "Dynamite". The "ay-o" bit in particular always made me think of "day-o" as in Harry Belafonte's "Banana-Boat Song."

Gradually

I succumbed--or perhaps I should say,

"submitted"--and started to think of "Dynamite" as

possessing a certain dumb genius. Especially the line that goes "I'm wearing all my favourite brands

brands brands brands".

But

looking from the vantage point of my forthcoming book Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction To Its Own Past, what's most striking and unsettling about the

now-pop is its not-so-now-ness: the fact that in the year 2011, mainstream pop sounds like the late Nineties.

Kids love this kind of stuff, of course. At the Nickelodeon TV channel's Kids' Choice Awards show in Los Angeles a few weeks ago, The Black Eyed Peas performed "The Time": what with the dazzling lights and deafening volume, it really was like a rave for children. We were there with our own kids: five-year-old Eli in particular is totally into the now-pop. Recently, driving in the car and flicking back and forth between pop stations and classic rock stations, he opined that Katy Perry was "rock'n'roll" but was quite adamant that The Stones's "It's Only Rock'n'Roll" was "not rock'n'roll". He wouldn't be budged.

Thursday, November 9, 2023

Let's Do The Time Warp Again (the Guardian, October 13th 1990)

Startled to be reminded just how long now - and how far back - I have been gnashing my teeth about retro-paralysis!

And in fact there's a riff using the "re" that I would later use in Retromania - not recycling, though, I don't think - it just re-occurred to me.

(And in fact someone else got there earlier, which I didn't know in 1990, or in 2010).

(I guess reinventing the wheel would be no small achievement, if you never even saw a wheel in the first place).

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

Thursday, November 2, 2023

the trap decade

[alternate ending to this 2010s-surveying piece on the Trap Internationale for The Face]

At the moment, trap – indisputably the sonic vanguard of mainstream pop – is locked in a vicious cycle: the desire of the underclass to become overlords. MCs could hardly be more explicit in their declaration of this deadly intent. In her #1 single “Bodak Yellow”, Cardi B talks about leaving behind stripping for rapping just like her spouse Offset talks about leaving behind trapping for rapping: “I don't gotta dance, I make money move… I'm a boss, you a worker, bitch, I make bloody moves.”

Listening to trap is paradoxical: immense creativity, flair, flamboyance, life-force, slamming right up against a deadening set of thematic constraints, somehow magically rewriting and re-rewriting the stale script into inexhaustible freshness. An absolute wealth of brilliance, an utter poverty of imagination. Rae Sremmurd may rap about being “Black Beatles”, but we’re a million miles from “All You Need Is Love” and “Imagine.”

The politics of trap revealed themselves, unfortunately, on the earlier Sremmurd single “Up Like Trump”, released in 2015. Swae Lee raps about reading Forbes like the Bible, Slim Jxmmi describes himself as a “money fiend,” and in the video, a Donald mask-wearing figure parties with the duo on the open top of a bus riding through Times Square. Speaking to Complex magazine at the time, Lee declared, “Donald Trump is cool…. I’m like, ‘That’s a cool motherfucker.’ He’s rich as fuck.” In a Guardian profile after their role model was elected, the duo defined Trumpism as “owning businesses, being bossed up” and seemed to have no regrets about making the song.

Rejecting party politics for apolitical partying, Jxmmi said that “young people wanna rage”. Sremmurd and their fans are about “living lit” and banging “our heads against the wall”. It’s a fitting cap to the trap decade: a President whose taste runs to nouveau riche glitz, who runs the White House like a Mafioso.

Friday, October 20, 2023

Umbrellas in the Sun (Disques du Crepuscule / Factory Benelux DVD)

VARIOUS ARTISTS

UMBRELLAS IN

THE SUN: A CREPUSCULE/FACTORY BENELUX DVD 1979-1987

(LTM )

The Wire, long ago

by Simon Reynolds

Founded in

Vintage videos can be embarrassingly dated, but the bulk of the material on Umbrellas gives off a sense of “limited means, effectively used.” ACR’s “Back To The Start” is a case in point, juxtaposing murky hand-held film of the band shaking their stuff in a field after nightfall with scenes of children dancing on the edge of an indoor swimming pool. The sallow lighting, oddly angled shots, and strange bodily geometries perfectly suit the group’s dislocated disco, its parched percussion draped with the bled-like-veal vocal pallor of Martha Tilson.

Josef K--like ACR, Northern punk-funkers with cropped hair and very clean ears--appear here performing “Sorry For Laughing” on a television pop show. The simple but clever twist is that the TV footage intermittently appears projected, bluescreen-style, onto a lump of Gak nestling on a girl’s bare stomach. Manipulating the goo, she distends the images of the band as they bob on her belly.

On a purely sonic level, Umbrellas’ highlight is Cabaret Voltaire’s “Sluggin’ For Jesus,” the lead track off 1981’s Three Crepuscule Tracks EP (arguably the group’s peak). Laced with American televangelist prattle, the entrancing Karoli-funk groove is accompanied by light-flickered images of the guys fondling their synths and, in Richard Kirk’s case, scritching away at a violin.

Close behind “Sluggin’” is the exquisitely plangent threnody for Ian Curtis that is The Durutti Column’s “Never Known” (although, for mystifying reasons, the track is here titled “Marie Louise Gardens”). With Vini Reilly generating such agonizing beauty of sound, all that’s required is the sparest of visuals, and that's what we get: the “missing boy” alone in a deserted public park at twilight, caressing the guitar strings with his finger-tips.

In scarcity terms, though, the gems here comprise the fabulous monochrome footage of Malaria! onstage performing “White Sky, White Sea” Tuxedomoon’s “Litebulb Overkill,” also live, but juxtaposed with Eurail travelogue footage (what looks like France seen from a moving train); and the 23 minute long film of a performance by Belgian funkateers Marine live juxtaposed with arty, kaleidoscopic visuals. Most known for the existensialist Chic of “Life In Reverse”, Marine’s entire aesthetic was based on the debut Benelux release, ACR’s emaciated cover of “Shack Up”.

Monday, October 16, 2023

Friday, October 13, 2023

Vermorel / Westwood

(for Artforum)

Fred Vermorel achieved both renown and notoriety for his

unorthodox approach to pop biography and as a theorist of fame and fandom. But

1996’s Vivienne Westwood: Fashion,

Perversity and the Sixties Laid Bare was his most eccentric statement

yet. For a start, the book was as much

about Westwood’s partner Malcolm McLaren as the legendary designer

herself. Her story was ably chronicled

in an imaginary interview weaved together from magazine quotes and half-remembered

ancedotes stemming from Vermorel’s long association with the punk couture duo

and the Sex Pistols milieu. But the book really came alive with the central

section: Vermorel’s memoir of Sixties London, when he and McLaren were

art-school accomplices. The longest and most vivid part of the book, it’s

packed with fascinating digressions on topics such as the semiotics of

cigarette smoking and the atmosphere of all-night art cinema houses. Among

Vermorel’s several provocative assertions is the claim that pop music back then

simply wasn’t as important as made out by subsequent false memorials to the

Sixties, but was regarded as unserious, a mere backdrop to other bohemian or

artistic activities. Posing as a profile

of a fashion icon, Vivienne Westwood

presents the reader with an outlandish blend of cultural etiology (it doubles

as an autopsy on the Sixties’s impossible dreams and analysis of its perverse

psychology) and triangular love story.

Vermorel and Westwood emerge as both still besotted with the incorrigible

McLaren, despite having each “broken up” with him long ago.

-

Simon Reynolds

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

me and Stereolab / me and Stereolab spoofed

Also wrote about this mini-LP in Spin that year

STEREOLAB

The Groop Played Space Age Batchelor Pad Music

Spin, 1993

Stereolab is one of the more intriguing groups to emerge from Britain's now-kaput dreampop scene. And this mini-LP is the group's most artful gambit yet. The title and packaging is a sly parody-homage to the "exotica" genre of the '50s, when tropical-scented, easy-listening albums by Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, etc, were designed so that the modern bachelor could (a) show off the stereophonic range of his state-of-the-art hi-fi, and (b) get his date "in the mood" before making his move.

It's a good joke, and a logical evolution for dreampop, since My Bloody Valentine, Cocteau Twins, Slowdive et al. always made for a consummate seduction soundtrack. Stereolab knows its musical history (it titled a recent single "John Cage Bubblegum") and on this album it explores the secret links between trance rock, ambient and Muzak. The result could be dubbed "kitschadelic": at once tacky and celestial, synthetic and sublime. On the opener, "Avant Garde M.O.R.", Laetitita Saider's serene and listeless vocals (midway between Nico and Astrud Gilberto) float through a fragrant mist of acoustic guitars, marimbas, and mood synths. "Space Age Bachelor Pad Music (Mellow)" could be the sort of jaunty, piped music you'd hear in a carpet store, but instead of being below the threshold of audibility, it's at full volume, so that its weirdness is in-your-face. The sequel, "Space Age Bachelor Pad Music (Foamy)" sounds like a Muzak vent that's fallen into a swimming pool.

The pace picks up on Side Two (New Wave), with "We're Not Adult Orientated". At first, the song's reedy Farfisa and staccato beat really do sound Noo Wave, but the track develops into something that's less like the Cars and more like the motorik style of the German band Neu!, a brimming, tingling, exultant onrush of sound that simulates the sensation of gliding down the Autobahn.

At times, Stereolab's parody of blandness is very nearly merely bland. But at its best, Stereolab is making the Muzak of the spheres.

I also wrote up the whole Melody Maker interview as a Q and A for my friends's independent magazine The Lizard (someone should digitize the whole six issue run of that, it was a much superior branching off a monthly full-colour publication called Lime Lizard, that itself had a lot of good stuff in it)

Stereolab

The Lizard

1994

SIMON REYNOLDS quizzes TIM GANE and LAETITIA SADIER about muzak, minimalism, motorik, Marxism and their fab new LP "Mars Audiac Quintet".

All the stuff that you were rehabilitating last year with "Space Age Bachelor Pad Music" and tracks like "Avant-Garde MOR" --muzak, mood and moog music, stereo-testing LPs, 'exotica'--is now tres hip. First there was Research's "Incredibly Strange Music" book/CD, now there's Joseph Lanza's "Elevator Music: A Surreal History of Muzak, Easy-Listening and Other Mood Song", Bar/None's anthology of avant-muzak legend Juan Garcia Esquivel (coincidentally titled "Space Age Bachelor Pad Music"), and so on, ad nauseam. All that stuff appears to be on the verge of entering the canon of acceptable, cool music.

Tim: "My only problem with 'Incredibly Strange Music', or at least the first Volume (I've heard # 2 is better) is that it seemed to be trying to attract people for kitschy, B-Movie reasons. You know how people have all the B-Movie posters but probably never saw the films? There's a difference between putting that music on at a party to make people laugh, and genuinely liking it as music. For me, muzak, moog, exotica, etc, it did a lot of things much earlier than other more respected, artistically serious forms of music did. Maybe for different reasons, but that doesn't take away from the fact that it did them, and created often shockingly original connections or juxtapositions of sound and genre. A lot of the reason why it's popular now is that it was very modern music."

So you're saying that it's the context of a music's creation, and of its consumption, that determines how seriously people take it? And that muzak is denigrated because of the way it was used, i.e. background listening?

"A lot of it was done for the crassest of reasons. Martin Denny's Moog album was obviously a cash-in, but what he created had a resonance that was far greater than if it had been done for high art reasons. It's kind of beyond high art or low art, it mixes up those categories. And the best music should be confusing, something you can't immediately decide what it's all about. And that applies to Stereolab--we want it to have lots of spaces where the listener has to decide 'is it avant-garde? Is it pop? Is it just self-indulgence?' Music can be surrealist if you look at it the right way.

"My big attraction to mood & moog music etc is that it's about the future. But 'cos it was made in the '50s and '60s, its idea of 'the future' was quite crass, but also full of optimism and infinite possibilities. And that's different to now, where the future isn't about infinite possibilities..."

It's about infinite anxieties.

"There's an attraction there, that people thought 'the future is gonna be fabulous, and wow, this is the weird music we're gonna hear there'."

Other elements that you draw on seem purely nostalgic, though, like all the ba-ba-ba-ba backing harmonies straight out of French '60s MOR.

"There's a problem with that, which is you can get too close to El Records--too cloying, and such a close copy of the original that it's pointless. The point is to take that music and juxtapose it with something else, something it's never been associated with before. So that you create your own personality and your own sound. There's no point in fetishising something, copying all the details precisely..."

Because you create something that just sounds dated... I suppose Stereolab's prime juxtaposition of hitherto antithetical elements is the way your sound fuses ultra-naff middle aged easy listening with ultra-cool underground rock: the trance-minimalism of the Velvets, Silver Apples, The Modern Lovers,Faust, Neu!, et al.

"My favourite music of all time is German music from the early Seventies. Laetitia too. Hearing Faust for the first time, it completely changed me. I don't know why, but that music has a power over me that is just a little bit above everything else. But that said, I don't like the Faust & Neu! thing to be bludgeoned to death."

A lot of your songs do rely on the motorik beat that Kraftwerk and Neu! used, though. That very metronomic, unsyncopated, uninflected rhythm, that's almost anti-rock'n'roll even though you can trace it back from Neu! through The Modern Lover's "Roadrunner", The Doors' "LA Woman" and Canned Heat's "On The Road Again", to Steppenwolf's "Born To Be Wild". Why do you love that motorik feel?

Laetitia: "You can never get bored with that beat. There's a discipline there, but never as an oppressor, always as something liberating. I find rock'n'roll really alienating, so I'm glad that Neu! exists."

Tim: "Krautrock is also very anti-muso--it has spaces where it's free form, but it's always done in a way that's non-musicianly. There's no solos or self-indulgence. It's spontaneous and exploratory, but not in that jazz sense of musicians playing to their full extent. I still don't know what the precedent for Neu! and Faust is. I always have this argument with some friends in France, who say 'well, the French don't really play rock music, it isn't really in the culture'. And I say 'well, until Neu! & Co, rock hadn't been part of German culture, but they took it and made it into something that no one in America or England had dreamed of. It was an expression of something very particular to that country, and yet it was far in advance of anything going on in the USA or the UK."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

'Ping Pong' is a critique of capitalism's in-built cyclical crises of slump and recovery, masquerading as Francoise Hardy-style Gallic girl-pop; "Wow and Flutter" is a chug-a-long World Of Twist meets Neu! anthem, whose chorus--"it's not eternal, imperishable, oh yes it will go"--gleefully anticipates capitalism's fall. So, Laetitia, are you a card-carrying Marxist?

Laetitia: "There is something there that I probably agree with. I've read 'The Communist Manifesto' and that was written over a century ago, but some of it still stands up. Some of it is obsolete, cos it was written at a certain time. I don't like the term 'being a Marxist' 'cos that makes it a religion or something. But it's true that Marx was a great thinker and there's a lot to be learned from his writings, even today"

Stereolab's ideas about integrating politics and pop are a helluva lot more sophisticated than most forms of agit-pop--specifically Manic Street Preachers, Rage Against Machine, Fun-Da-Mental, where there's a rather pat equation of hard politics and hard aggressive music. That whole combat rock posture. The trouble with that kind of agit-pop is that the punters who buy into that ethos seem to think that buying a CD or a concert ticket (and then standing in a crowd of likeminds) is somehow a 'contribution to the struggle'.

Tim: "All records are about self-image, in that you buy the music that reflects your sense of yourself and position in the world. It's about wanting to belong to a certain group. And that's not something you can change."

Laetitia; "That approach is not subversive at all, because it's obvious. So screaming = 'angry'. The real subversion lies where you don't expect it."

So Stereolab's political contribution resides in fostering a subtle, insidiously effective climate of critical awareness, as opposed to constructing a tenuous, shallow solidarity via slogans and calls-to-arms?

Tim: "There has to be a certain amount of thought process involved on the part of the listener. Like Dada--when they wanted to combat the First World War, instead of putting up posters that said 'We are against the War', they transformed it into an art thing that wasn't immediately or literally about the war, but evoked its horror and absurdity. The Situationists did the same thing, with 'detournement'".

I was a big fan of the Situationists when I was younger, having read of them in interviews with Malcolm McLaren and initially assuming they were some fabulously subversive, evil rock band called The Situationists. Anyway, like you, I was very taken by their playful, mischievous forms of subversion--like pasting speech bubbles over advertising hoardings so that the people spouted anti-bourgeois rhetoric or surreal poetry. At the same time, the Yippies in America were doing similar kinds of agit-prop pranks, like proposing a pig for President. Eventually, however, the far-left and anarchist radicals of the late Sixties realised that Dadaist wit was no match for the batons and bullets of state power. And many of the idealists who were mobilised by 1968 evolved into terrorists units--the Weathermen in American, the RAF in Germany--and waged war on the State, fought fire with fire. I mention all this because I remember Laetitia once said in an interview that she believed revolution would necessarily involve bloodshed and violence.

Laetitita: "It's inevitable. The other day I was thinking about this, wondering: 'if revolution really does happen, what do we do with people like John Major? Do we kill them? Do we brainwash them? Do we get them to mop the streets?' When it gets that concrete, it's 'fucking hell!' Cos that's a hell of a responsibility. And that's why such a lot of revolutions, like the Maoists, involved so much blood and slaughter."

I sometimes whether the problem is not capitalism versus socialism, but industrialism itself. The Communist Bloc, as we all know, was state capitalist, not socialist--the surplus value generated by workers went to the Nation instead of private shareholders, which just meant that it went to finance the USSR's military-industrial complex. In some respects--like polluting the environment--Soviet state capitalism was worse than its Western equivalent. But who knows, even if 'proper' socialism was achieved--with real 'soviets', i.e. workers councils--maybe life would still be dreary. Because you'd still be living in a managerial, bureaucratic society, you'd still have people working on conveyor belts or cleaning toilets with minimum job satisfaction. Anyway, I guess what I'm trying to ask is: do you have a mental picture of utopia, of a perfectly run and just world?

Laetitia: "No, I don't have such a picture. I don't think there could ever be a perfect world. At the same time, there's plenty of scope for a much fairer system. At the moment 6 percent of the world owns 90 percent of the wealth. All that wealth should belong to nobody and to everybody! It's completely mathematical, things just don't add up in our system. And that's why there's slumps, that's why there's wars, and all these other dreadful things. So I can imagine a much better world. But when you get down to practical details, it's harder...."

I once asked another band this question (bizarrely enough, Dinosaur Jr, of all people...) Can you imagine a situation where you would take up arms against the state?

Laetitia: "The thing is that EVERYTHING must be used--your cleverness, the fact that you might be an acrobat... Everything from weapons to the little money that you have that can be invested properly, to cunning tricks. So, weapons, yes. They have a whole army out there, a police force, and they don't hesitate to use them."

Maybe the link between your interest in the Situationsts and the muzak & moog records is that very '60s sense of anticipation and excitement about the future. The Situationists' utopia was predicated on the idea of total automation leading to the abolition of work and a life of perpetual play. Which isn't so far from the idea of the comic book idea of the future, where your robot-butler brings your fried egg. The sleeves of the Moog records are full of techno-phile/neo-philiac, this-is-the-future iconography. It seems so naive now, but it's strangely touching and poignant.

Tim: "It's just the idea of the future as strange because it's so totally non-traditional."

Whereas now we know the future will be just like the past, only even more delapidated, and with hi-tech surveillance cameras in most urban areas.

Laetitia: "That's the trouble, people don't believe in the future, they don't believe in revolution, or a better world, anymore. They don't even want a better world. So therefore it's not gonna happen. You have to want it first and to think it's possible, in order to make it come about."

&&&&&&&&&&&&&

This isn't even all my Stereolab writing! Did a thing on them and the Charles Long exhibition The Amorphous Body Study Center for Artforum (the CD they did of the music for that might be my single favorite album of theirs); a review of Emperor Tomato Ketchup, a feature for Rolling Stone around that album.

There can't be many artists I've written more about (Goldie? Who also got a single of the week the same week as 'Crumb Duck'. Young Gods? The Smiths / Morrissey, I guess... Aphex Twin... in recent-ish times Ariel Pink. And oddly Royal Trux)

Sunday, October 1, 2023

Friday, September 29, 2023

Sunday, September 24, 2023

In The Neighborhood - Ernest Hood

Ernest Hood

The Nation, November 5 2019

by Simon Reynolds

South Pasadena, where I live, looks like the archetypal American suburban dream. Craftsman houses from its tree-lined streets featured in Thirtysomething and Back to The Future, to name just a couple of the town’s many screen cameos. And just a little way down our road, there’s a darling little house that’s frequently used in TV commercials. The film crews, craft services, and costuming trucks with their racks of garments were an amusing novelty at first. I particularly enjoyed the Christmas commercial, fake snow covering lawns while the sun shone down on yet another perfect 73-degree LA day. But then it got to be a drag, all those large vehicles parked up and down the road. The telegenic image of our street as an ideal neighborhood was detracting from the reality.

These mildly aggrieved thoughts flickered through my mind while listening to Ernest Hood’s Neighborhoods, a gorgeously tender sound-portrait of the all-American suburban idyll, originally released in 1975 but now lavishly reissued as a double-disc vinyl set. Woven out of plangent ripples of zither, wistful synthesizer refrains, and children’s voices field-recorded by Hood in the streets of his own Portland neighborhood, the album can’t help reminding you of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Sesame Street, and the halcyon mood, if not, the sound of Vince Guaraldi’s jazzy Peanuts score.

The only album Hood ever released, Neighborhoods is considered by some to have invented ambient music a couple of years before Brian Eno. “Musical cinematography” was Hood’s own description in the original liner-notes. “It’s like watching a movie—you get establishing shots and you’re pulled in,” says his son Tom Hood by phone from South East Portland, where he still lives. “In that sense, it’s not ambient, because with that you’re meant to tune out, but Neighborhoods makes you focus.”

Each track is evocatively titled—“Saturday Morning Doze”, “The Secret Place”, “Night Games”—and comes with an impressionistic description designed to trigger mental movies, like the reference to “cards flapping in the bike spokes” in the text for “After School.” Sometimes the sense of place is very particular: Hood’s “caption” for “From the Bluff” mentions Portland’s Oaks Amusement Park and the “distant marshes” of the Willamette River. Layer upon layer of nostalgia enfolds the record: it’s partly inspired by Hood’s memories of his own pre-WW2 childhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, but the album also features snippets of his 4-year-old children recorded in 1950s Portland. Playing Neighborhoods today only adds extra layers: the charmingly dated synth is redolent of 1970s PBS, while each listener will affix personal memories date-stamped to the decades of their own childhoods and linked to their hometowns in other states or countries.

Hood was a professional musician who played guitar in jazz bands until polio - which he contracted in the late 1940s when still a young man – made the travelling lifestyle unworkable. He carried on doing session work and briefly ran a Portland jazz club, but increasingly his energy was dedicated to the obsessive documentation of everyday soundscapes. Even before reel-to-reel tape machines became readily available, Hood used an earlier technology, the wire-recorder—a machine that captured sound by magnetizing points on a thin steel wire. He captured bird song and frog noises and would give tapes of outdoor sounds to ill people who couldn’t leave their houses. Hood had a particular obsession with the sonic ambience of covered bridges and would make expeditions to record and sketch Oregon’s surviving examples. Tom Hood recalls making a pilgrimage with his father to his ancestral hometown in North Carolina and recording the entire road trip. He is currently combing through his dad’s vast unruly archive, digitizing tape reels with a view to possible further releases.

Hood’s preservationist impulse seemed to stem in part from an acute susceptibility to nostalgia. This pained awareness of the passage of time also expressed itself through a hostility to the modern world’s noise pollution. He wrote letters to local newspapers complaining about the assaultive properties of contemporary music. A flavor of this invective can be gleaned from the Neighborhoods liner note, which passingly rails against “commercial music purveyors” and “plastic novelty music played on military weapons.” One of Hood’s pipedreams was a low-power, small-radius radio station that would play 1920s and 1930s music, carefully leaving 30-second gaps between each 78 r.p.m. platter to allow for proper musical digestion. That never transpired, but Hood did help to found the volunteer-run local radio station KBOO FM, to which a portion of the proceeds from the Neighborhoods reissue will go.

*

Hood strikes an “it takes a village” note when he writes about how the record will trigger pangs in listeners no matter “which neighborhood you sprouted,” describing the project as the paying of “a debt to some beautiful and loving people…. older folks… who put up with my childhood pesters [and] played such an important role in the formation of comfortable memories.” Hood emphasizes that while the record is not something to play in gregarious situations like a party, “it is a social record in that it reminds us of the fact that most of us made our first social contacts… in our neighborhood streets.”

Reading Hood’s words while listening to his shimmery cascades of electronic instrumentation, which often have the flashback quality of a cinematic dissolve, I wondered to what extent the close-knit, placed-based nurturance that Hood celebrated still applied. I also wondered if I’d ever experienced anything like it. Britain has its romanticized myths of working-class community: a sentimental folk memory of housewives chatting over garden fences in back of terraced housing, next-door-neighbors popping round to borrow cups of sugar, and so forth. But once you go up the class ladder, self-contained privacy becomes the norm: as their descriptors imply, semi-detached and detached houses indicate a weakening of the social bond. That’s what it was like where I grew up, an English commuter town surrounded by fields and woodland but close to London: people were civil but largely kept to themselves.

Ascend some more rungs and you reach the super-rich, who lead completely de-territorialized lives, thanks to their multiple homes and cunning ways to avoid paying tax in the places through which they pass. Privilege is measured by the extent to which you can avoid public space and public transport (private planes and private elevators). You can live as though the humans immediately surrounding you do not exist. Hence the vogue in the posher parts of London for the ultra-wealthy to expand their properties underground, excavating subterranean floors for swimming pools and gyms, blithely disregarding the noisy and dirty disruption caused to everyone else in the street by the building work. The ultimate assault on the idea of “neighborhood” is owning a property without living there, ghosting out an abode as a vessel for investment while pricing out regular folks from the area. If rootless transience—a nomadic lifestyle that mimics the free movements of international capital—is privilege, then conversely it’s those at the bottom who are most territorialized, literally kept in their place.

Class is a factor, but so is age. Young people who move to cities are partly attracted by the freedom of dislocation, the chance to escape the bonds and binds of belonging to a community. As a twentysomething living in London in the 1980s and 1990s, I recall being barely on nodding terms with neighbors in the various apartment blocks or subdivided houses in which I lived.

*

The neighborhood as an extension to family that the uncannily named Hood celebrated seems to exist largely for children. That’s when I remember it as a social fact in my own life: you played with whoever was near to hand. And it was only when I had children myself that I really started to feel like I lived in a neighborhood. That was in the East Village of New York, a city that otherwise would seem to represent the ultimate in disconnection. Yet both within our 12-story apartment-block coop and in the surrounding streets, there was a pleasant sense of community. Children were the glue, or rather the dissolving agent, in terms of interpersonal boundaries. You talked to people with whom you might not have much in common simply because your kids played together. Halloween provided the treat of peering inside the apartments of people on other floors. Compared with the East Village’s jostling intimacy, suburban LA is diffuse, although PTAs, Little League, and “home churches” counteract the centrifugal tendencies of a spread-out, non-pedestrian city.

Although the freedom for kids to wander around their neighborhoods that some of us enjoyed in the 1960s and 1970s has largely been curtailed by anxious parents, small children still have that here-and-now, face-to-face orientation. But as soon as they get phones, bonding systems emerge that are steadily less related to geographic proximity. They start to resemble adults, with friendship systems organized around taste or interests. My own “true” neighborhoods for some time now have been unmoored from real space and real time: internet-based forms of conviviality and parochialism oriented around musical or intellectual concerns, gathered around blog clusters or message boards. A while back I started jokily addressing readers of my own blog as “parishioners.” And it would have been through a music-sharing blog or an online collective audio-archive that I first heard Neighborhoods some years ago.

Originally released on his own Thistlefield imprint in an edition of a few hundred, offered for mail-order sale at $5.95 but mostly given away to friends, Neighborhoods gradually found its true audience as it circulated in used record shops, then reached the internet. Hood died in 1991, long before he could see the rediscovery of his one-and-only album. I don’t know if he would recognize file-sharing as a form of neighborliness. But he would surely have felt delight and vindication at its long and winding ascent to cult legend.

Monday, September 18, 2023

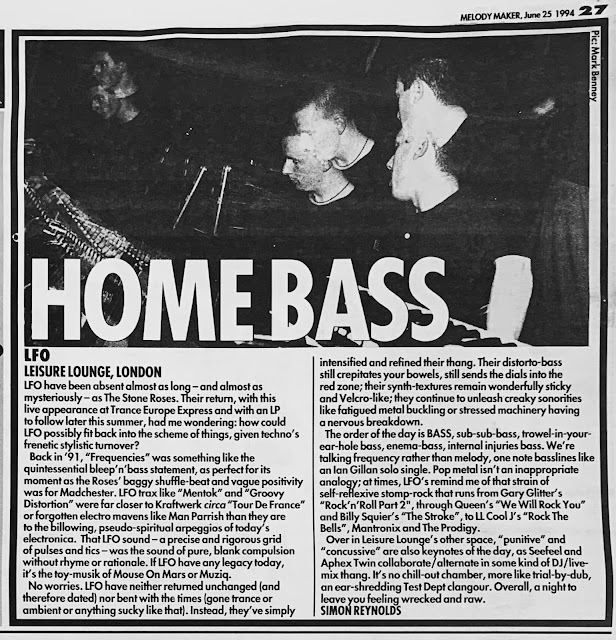

El Ef Oh!

Oddly, never made the connection between the electro roots of Mark 'n' Gaz (who met as members of rival teams in a breakdance contest) and the fact that Tommy Boy put out Frequencies in the USA.

Tommy Boy also put out 808 State's Ninety, in a remixed form.

LFO

Sheath

(Warp)

Observer Music Monthly, 2003

It’s a tough time for dance music believers. Mainstream house culture has imploded, with superclubs closing, dance magazines folding, and average sales for 12 inch singles on a steady downward arc. The more cerebral end of home-listening electronica suffers from stylistic fragmentation, overproduction (there’s just too many "pretty good" records being made), and the absence of a truly startling new sound (even a Next Medium-Sized Thing would be a blessing at this point). Trendy young hipsters think dance culture’s passe and really rather naff: these days they’re into bands with riffs, hooky choruses, foxy singers, and good hair, from neo-garage groups like The White Stripes to post-punk revivalists like The Rapture.

Little wonder, then, that the leading lights of leftfield electronica have been looking back to the early Nineties, when their scene was at the peak of its creativity, cultural preeminence, and popularity. There’s been a spate of retro-rave flavoured releases from the aging Anglo vanguard--a reinvocation (conscious or unconscious, it’s hard to say) of the era when this music was simultaneously the cutting edge and in the pop charts.

LFO’s Mark Bell is a case in point. Today he’s better known for his production work with Bjork and Depeche Mode, but back in 1990, he was one half of a duo who reached #12 in the UK singles charts with their self-titled debut "LFO". This Leeds group pioneered a style called "bleep", the first truly British mutation of the house and techno streaming over from Chicago and Detroit. In 1991 they released Frequencies, the first really great techno album released anywhere *(unless you count ancestors Kraftwerk, alongside whose godlike genius LFO’s best work ranks, if you ask me). Just about the only bad thing about Sheath, LFO’s third album and first release for seven years, is its title, which I fear is being used in its antideluvian meaning of "condom" (only "rubber johnny" could have been worse). Really, this record should be called Frequencies: the Return.

Deliberately lo-fi opener "Blown" instantly transports you back to the era of landmark records like Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works 1985-91. All muddy heart-tremor bass, creaky hissing beats and tinkling, tingling rivulets of synth, it has the enchanted, misty-eyed quality of those childhood mornings when you wake to look through frost-embroidered bedroom windows. "Mokeylips" teems with fluorescent pulses and those classic LFO textures that seem to stick to your skin like Velcro. As bracing as snorting a line of Ajax, "Mum-Man" is industrial-strength hardcore of the kind that mashed-up the more mental ravefloors in ’92. With its robot-voice dancemaster commands and videogame zaps, "Freak" harks back further still to LFO’s Eighties roots as teenage electro fans body-popping and spinning on their heads in deserted shopping centres. "Moistly" shimmers and surges with that odd mixture of nervousness and serenity that infused the classic Detroit techno of Derrick May and Carl Craig. And the beat-less tone-poem "Premacy" pierces your heart with its plangent poignancy.

Electronic music may be suffering from the cruel cycles of cool at the moment, but Sheath (ugh, I really don’t like that title) shows that music of quality and distinction is still coming from that quarter. Yet more proof (if any were still needed) that all-instrumental machine-music can be as emotionally evocative, as sensuously exquisite, as heart-tenderising and soul-nourishing as any rock group you care to mention. (Like for instance Radiohead, whose Thom Yorke, as it happens, was a huge fan of the Northern "bleep" tracks released by Warp in the early Nineties). One can only hope this album finds the audience it deserves.

And some bits from my 2008 FACT celebration of Bleep

LFO

"LFO"

(Warp, 1990)

Kraftwerk reincarnated as a pair of teenage ex-breakdancers from Leeds, LFO's Mark Bell and Gez Varley took bleep into the Top 20 with this immortal classic. Portentous and momentous like "Trans-Europe Express", the opening synth-chords make you feel like you're being ushered you into the presence of greatness. Then that dark probe of a bassline bores its way into the depths of your brain, via your anus. LFO would go on to record the immaculately inventive Frequencies, one of electronic dance music's All Time Top 5 Albums.

LFO

What Is House EP

(Warp, 1992)

Where better to end than with LFO voicing the question originally raised by bleep itself--just how far can house music be stretched and still be house? With its gnarly synth and electronically-distorted spoken-not-sung vocal, the title track sounds like the Fall if Mark E. Smith was reborn as a 20 year old South Yorks pillhead. The concise lyric pays homage to "the pioneers of the hypnotic groove"--from Phuture, Fingers Inc and Adonis to Eno, Tangerine Dream, YMO, Kraftwerk and Depeche--but like all tributes implies: we're more-than-worthy inheritors.

* the first really great techno album

Is this unfair to 808 State, who did Ninety a year earlier? Maybe, but not really, as I don't really think of that album as techno - it's more like a dreamy, ambient-tinged house record. Great album, and one that has lasted for me whereas Ex:Cel (which is slightly more techno, even has some hardcore-aspiring tunes on it, and came out in '91) hasn't endured.

Unfair to anyone else? Not sure what month it came out in '91, but Ultramarine might have pipped LFO to the post - but then again, Every Man and Woman Is A Star isn't really techno, is it? It's more acid meets chillout meets pastoral fusion.

Also that year was Orbital's debut - but Frequencies wipes the floor with that.

LFO labelmates Nightmares on Wax also debuted at album length in 1991 but Word of Science is already trying to expand beyond bleep and touching on the downtempo smoker's muzik of their later discography.

Unique 3's Jus' Unique came out in 1990. There's great stuff on it: deep-bleep like "Phase 3" and "Digicality", tuff little unit of a toon "Code 0274", plus the classic singles up to that point. Overall, though, it's not quite on a par with Frequencies - bit too much of an eclectic sprawl, with some Rebel MC-ish rap tracks that are fun but a bit dated.

DHS did The Difference Between Noise and Music in '91 - I'll have to give that a relisten. Possibly a real contender against LFO. (I did give it a relisten and it's pretty interesting stuff but not as consummate as Frequencies)

Oh, blimey, how could I forget - there's A Guy Called Gerald's Automanikk, from 1990. I don't recall it quite being on a par with Frequencies, or even with Ninety (the apposite comparison). The great, all-time Gerald album is Black Secret Technology, with '92 's 28 Gun Bad Boy also a strong statement.

A couple of contenders - 4 Hero's In Rough Territory (but it's before they've really found their path, and I don't remember it being a great album - a bit rough, in fact, and not ruff-rough). And then Nexus 21's The Rhythm of Life (from as early as '89), which I think is pre-bleep and when they are still very much Detroit-emulative and specifically Kevin Saunderson fanboys.

Where else could we look for pipping-Frequencies-to-the-post possibles? Detroit? I don't think any of the major artists had done an album-album by that point. Germany?

Even more consistent and long-running LFO / Warp / bleep + bass celebration (for the benefit of certain folks who should know better, and in fact, I wager, actually do know better)

Warp Influences / Classics / Remixes

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Warp 10+1 Influences

Warp 10+2 Classics

Warp 10+3 Remixes

(Warp/Matador)

Spin, 1999

by Simon Reynolds

UK rave started out as that strange thing--a subculture based almost entirely around import records. In 1988-89, British DJs had several years backlog of feverish house classics to spin, plus fresh imports from Chicago, Detroit and New York every week. Homegrown tracks, mostly inferior imitations, couldn't compete. All this changed by early 1990 with a UK explosion of indie dance labels and the emergence of a distinctively British rave sound that merged house with elements of hip hop and reggae. Based in the Northern English industrial city Sheffield, Warp was the greatest of these dance independents, and one of the few to survive the era. Released to commemorate the label's tenth anniversary, these three double-CDs showcase the sharp ears and canny self-reinvention skills that have ensured Warp's longevity and continued relevance.

Warp's first phase of cool came as the prime purveyor of "bleep-and-bass"--a style that owed as much to electro's pocket-calculator melodies and dub reggae's floorquaking sub-bass as it did to acid house's trip-notic compulsion. Much of Classics sound like a direction Kraftwerk could have followed after 1981's Computer World. Sweet Exorcist's "Clonk," for instance, is like Ralf und Florian lost in the K-hole, an inner-spatial maelstrom of weird geometry and precise derangement. Ranging from Tricky Disco's cartoon-quirky almost-pop, through the cold urgency of LFO and Forgemasters, to Nightmares On Wax's proto-darkside disorientation, Classics is a fabulous document of a forgotten era of UK dance culture. Fortuitously, bleep-and-bass sounds fresher than ever today, chiming not just with the electro renaissance within techno (i/F, Ectomorph) but with the dry, drum machine beats, geometric stab-riffs, and chilly-the-most synth-tones audible in recent rap/R&B--Cash Money bounce boys like Juvenile, Ja Rule's "Holla Holla", Timbaland/Missy/Ginuwine.

Influences mostly consists of sinister acid house from the import-dominated era of Brit-rave. But two inclusions locate the blueprint for early Warp more precisely in that late Eighties phase when twilight electro merged with the harder, tracks-not-songs side of house. New York outfit Nitro Deluxe's 1987 "Let's Get Brutal" is a vast drumscape underpinned with tectonic shock-waves of sub-bass and topped by a shrill, staccato keyboard vamp made out of a vocal sample played several octaves too high. Kickstarted by the hilarious vocoderized mission statement "we are the original acid house creators/we hate all commercial house masturbators," and motored by a miasmic bassline that recedes into the mix then swarms back to subsume your consciousness like malevolent fog, Unique 3's "The Theme" was actually the first bleep tune; as their old skool name suggests, the group was a North of England B-boy crew turned ravers.

Where Influences works as a superb primer in early house, Remixes intentionally fails to document the post-bleep Warp that most people know-- revered home of Aphex Twin, Black Dog, Autechre and Squarepusher, those godfathers of IDM (Intelligent Dance Music, or dance music you can't really dance to). Instead, the double-CD aims to capture the shape-shifting spirit of the post-rave network (with its one-off collaborations, multiple aliases, and omnivorous eclecticism) by subjecting some of Warp's finest to remixes from a host of suspects usual and unusual. UK post-rockers Four Tet, for instance, take a track from Aphex's Selected Ambient Works Vol II and turn what was originally as lustrous and near-motionless as crystals forming in a solution into a frisky work-out reminiscent of an over-caffeinated Tortoise.

Highly listenable, the double-CD nonetheless suffers from the cardinal drawback of modern remixology--rather than enhancing the beloved original or locating some latent potential within it, the remixers almost invariably replace it with an all new track containing only a token trace of the ancestor. In that sense, Warp 10+3 Remixes effectively evokes the present moment in electronica, where too many producers have got so infatuated with technique, they've lost contact with the dancefloor. Whereas Classics captures a lost moment of perfect coexistence between auteurism and popular desire, when experimentalists (like Sweet Exorcist's Richard H. Kirk, formerly of Cabaret Voltaire) briefly got on the good foot.

Friday, September 15, 2023

Mo' Wack

Various Artists

Royalties Overdue

Mo' Wax

Melody Maker, June 18 1994

by Simon Reynolds

Headz 2

(Mo Wax)

Village Voice, 1996 (remixed slightly for Faves of 1996)

by Simon Reynolds

In the age of compilation gigantism, Headz 2 dramatically ups the ante. Mo

Wax's latest anthology consists of not one but two separately sold double-CD's (or two quadruple albums, boxed like Wagner's Parsifal), which contain nearly five-and-a-half hours of music spanning not just trip hop but leading innovators in drum & bass, techno, art-rap and electronica. Before I even saw these dauntingly oversize collections in the stores, I was put off by the air of hubris and self-congratulatory connoisseurship hanging over the project. When I saw them, the deluxe vinyl sets instantly reminded me of those calfskin-bound, gilt-inlaid editions of Dickens (sold through mail-order ads that appeal to "your unstinting pride"), which remain unread on the shelf but testify to an

interest in being cultured. In Headz case, the word is subcultured.

Despite their garish abstrakt covers, the vinyl Headz also resemble headstones,

perhaps because Mo Wax supremo James Lavelle has herein constructed a kind of mausoleum of late '90s "cool". Appropriately, the music itself is sombre and

subdued, mostly cleaving to the trip hop noir norm: torpid breakbeats, entropic

sub-bass, dank dub reverb. (When it comes to non-junglistic breakbeats, give me the rowdy, rockist furore of the Chemical Brothers, Fatboy Slim and their amyl brethren, any day). The same Mo Wax kiss-of-def that resulted in Luke Vibert's only uninteresting release to date affects contributions from the likes of Danny Breaks, whose abandons his normal hyper-kinaesthetics for the idling headnooding tempo of "Science Fu Beats". (Perking the track up to 45 r.p.m improves this, and several other tracks, considerably).

Mo Wax belong to what you might call the "good music society", or more

precisely, they belong to a specific "good music society" which dates back to

the "eclectic" list of influences on Massive Attack's "Blue Lines" (wherein PiL,

Mahavishnu Orchestra, Isaac Hayes and Studio One coexisted in smug

self-congratulation). The sensibility is pure fusion: "it's all music, man",

"what kind of music don't I like? -- just bad music!". Every area of music has

it own "good music society", its little cabal of cognoscenti, what Kevin Martin

calls the "taste police": Junior Boys Own for deep house, Creation (in the late

Eighties at least) for leather-trousered rock, Grand Royal for white American

B-boyism. Each maintains a canon of cool, and as with all canons, what is

excluded is as significant as what is included. What is excluded tends to be

both the vibrantly vulgar and the genuinely extremist/out-there: neither The

Sweet nor Stockhausen make it. (Although Pierre Henry, bizarrely, has been

canonised --as a pioneer of E-Z listening alongside Jean-Jacques Perrey!!!).

The first was bad enough - so I guess I'd assumed that that would have been it

But no, no, they persisted after Psyence Fiction (yuk wot a title) - there's something like FIVE subsequent UNKLE albums!

And what's worse is that they get increasingly rocky, involving such as Josh Homme from Queens of the Stone Age

Like Lavelle started buying into this really naff idea of rock rebellion and intensity and authenticity

Like a less tastefully executed version of the Death in Vegas approach - a studio assembled simulacrum of rock, without the actual rhythmic engine of band-energy powering it

I guess it shows the odd lingering prestige of rock - and especially the punk strand within rock - as the ultimate stand-in for rebellion and individuality, which continues to exert its thrall over people who've come up through hip hop or dance music, and whose creative procedures are radically different

For some reason deep in their hearts their burning desire seems to be to collaborate with Noel Gallagher (as with Goldie circa Saturnz Returnz on "Temper Temper") or Pete Doherty or somebody like that, despite being light-years ahead sonically of those guys.

The other thing I gleaned from the doc - and Lavelle's embrace of rockism - was that he'd managed to convince himself that being a curator really is the same as being a creator - that's there's really nothing to writing songs, creating a distinctive band-sound, a band-voice.

All you need is some famous pals, and some connections - and taste, and attitude

Simply convening the ingredients would somehow generate vibe in itself, hey presto, through the magic of chutzpah

Wrong!

Hubris 101: not knowing your limits, the nature of what you are actually good at (in his case, arguably at any rate, branding, packaging, spotting talent in others i.e. Shadow, Krush, building a buzz)

Yet despite this, UNKLE is still going - there's a new album out soon - The Road: Part II/Lost Highway - a "filmic" affair whose cast includes the Clash’s Mick Jones, Dhani Harrison, Editors’ frontman Tom Smith, The Duke Spirit’s Leila Moss, Mark Lanegan, Keaton Henson, Queens Of The Stone Age’s Jon Theodore and Troy Van Leeuwen, Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds vocalist Ysée, Brian Eno collaborator Tessa Angus, producers Justin Stanley and Chris Goss, BOC, spoken-word contributions from legendary Scottish actor Brian Cox, and more

First single

Press release:

“Once you have walked the road, everything becomes clear,” says Elliott Power on the Prologue to the sixth album from genre-bending pioneers UNKLE. ‘The Road: Part II / Lost Highway’ is the sound of an artist forever in transit on life’s journey of discovery.

“My work has always had an eclectic essence and soundtrack-influence in its structure,” says Lavelle. “If you go through the back catalogue, there’s a continuity between the motion and the ambition of the sound. Ideally, you’re constantly collaging and sampling elements of what’s relevant at the time to create something new.

“Now, there’s a lot more freedom. When I first started, the walls between genres in front of you were a lot greater to climb. We’re at a much more open-minded and eclectic place with music now.”

"I started doing a show on Soho Radio last year, which made me think about playing records in a different way,” says Lavelle of his life after ‘Part I’. “It wasn’t about trying to make people dance in a nightclub. It was a breath of fresh air, and about playing a more eclectic mix. ‘The Road Part 2’ was made in the same way – it’s a mixtape and a journey. You’re in your car, starting in the day and driving into the night. The language of it was for it to be the ultimate road trip.

He continues: “It’s the mid-part of a trilogy. The first record is like you’re leaving home; you’re naive and trying to discover. There are elements of my early days in there, as well as a bit of everything since. There’s an optimism and excitement to it, as there was with me having to direct this project alone for the first time.

“This record is the journey. You’re on the road, out there in the world. There are let downs, highs, lows, love, loss and experiences. The third record to come is basically about coming home; wherever that may be."

With the album split into two acts each with a beginning, a middle and end, the trips from light to dark, from brute force to tenderness make for both the full arc of the adventure and suites to be enjoyed separately. It’s a bold, assured and confident collection – from the Americana of ‘Long Gone’, to the Kanye West ‘Black Skinhead’ - inspired ‘Nothing To Give’, the alt-orchestral rush of ‘Only You’ to the guitar-heavy mantra of ‘Crucifixion/A Prophet’ and the electronic child’s lullaby of ‘Sun (The)’ – via covers of ‘The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face’ made famous by Roberta Flack and the ‘guilty pleasure’ of the euphoric ‘Touch Me’ by Rui Da Silva. Helping to travel further down the myriad avenues of UNKLE’s sound are the full spectrum of collaborators and guests.

‘The Road: Part II/Lost Highway’ welcomes The Clash’s Mick Jones, Dhani Harrison, Editors’ frontman Tom Smith, The Duke Spirit’s Leila Moss, Mark Lanegan, Keaton Henson, Queens Of The Stone Age’s Jon Theodore and Troy Van Leeuwen, Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds vocalist Ysée, Brian Eno collaborator Tessa Angus, producers Justin Stanley and Chris Goss, BOC, Philip Sheppard and artist John Isaac among others – as well as spoken-word contributions from legendary Scottish actor Brian Cox (who used to be Lavelle’s landlord) and Stanley Kubrick’s widow Christiana, who leant her trust and voice to Lavelle following his acclaimed exhibition to the seminal director. The two names who crop up most throughout the record however are rising West London singer and producer Miink and experimental rapper Elliott Power.

“They’re just both so incredibly talented, and everything I love about London right now,” says Lavelle. “I’ve been playing a lot with going back to sampling and going back to certain aesthetics from when I was first buying records and DJing, then to mix that with something contemporary. They’ve helped me create this ‘Bladerunner meets London Soundsystem’ kind of vibe.”

But then, Lavelle has always been an artist as inspired by the past as he was racing towards the future.

“The way that things are now are what we were always doing with Mo’Wax,” says Lavelle. “The legacy was that we broke down barriers, took down everything culturally-lite and put it into something. Now street culture is the predominant visual culture of the world. It’s mad to think that Supreme is more popular and recognised than Louis Vuitton. Every major label and rapper is making sneakers and toys. At the time it was seen as vanity and gimmicky, but look at the way culture is now. That’s what we started.”

The striking artwork of the hooded knight that adorns the sleeve on 'Lost Highway' is by celebrated artist John Stark – renowned for drawing upon magical realism and using the more mystical elements of the past to reveal something profound about the present.

"It’s about the yin and yang, night and day, the rolling journey," says Lavelle of the artwork. "Here's a Ronin-like, lone warrior. It represents what it means for me to be going out into the world and finding myself."