AMM

AMMmusic

Melody Maker, 1989

by Simon Reynolds

Nowadays, we're familiar with the idea of "free music": music that abandons the shackles of training and technique, in an attempt to propel both player and listener outside history, beyond culture, and into a Zen no-where/no-when. We've heard this rhetoric reheated and this approach rehashed by all manner of marginal rock iniatives: the Pop Group, early Scritti, Rip Rig and Panic, Einsturzende, and currently God. So it's both chastening and valuable to go back to when the idea was more or less originated: 1966, a group called AMM who made (and still make) "music as though music was being made for the first time". This is their first album,

originally released by Elektra Records, in those heady days of the counter culture when people thought this kind of thing might just be marketable. Recommended have reissued it complete with segments from the original sessions which never

made it onto vinyl.

As AMM member Eddie Prevost puts it in his copious and illuminating sleevenotes, AMM music "gently but firmly resists analysis". Listening the mind's eye swarms with an

inferno of images: gales, tidal-waves, timber-processing plants gone mad, a monsoon of stalactites. But in the end, adjectives and metaphors sheer off the obtuse, elusive, jagged surfaces of the sound. AMM music may initially seem impenetrable, but it sure as hell penetrates you. Soon, the desired state is instilled in the listener: a rapt vacancy somewhere between supreme concentration and utter absent-mindedness. Prevost describes how AMM music was widely assumed to be "religious", and how in some senses this was true. Fully immersed, you can escape the inhibitions and repressions that hold you together as "one", and revert to a

primal state of manifold unbeing. In it, you can be everything and nothing.

There was a whole buncha theory behind this music--ideas like "all sound can be music", "silence can be music", elements of Buddhism (meditation without the mysticism). But ultimately words are neither needed nor enough. For a while

AMM used to discuss their music endlessly, but soon they stopped, just turned up, played and went home without a word. And it's not necessary to bone up in order to bliss out. Just come with an open mind, and leave, 74 minutes later, marvelling at just how opened a mind can get.

"there are immaturities, but there are immensities" - Bright Star (dir. Jane Campion)>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "the fear of being wrong can keep you from being anything at all" - Nayland Blake >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> "It may be foolish to be foolish, but, somehow, even more so, to not be" - Airport Through The Trees

Monday, April 28, 2008

RADIOHEAD

Kid A

director's cut, Spin, 2000

by Simon Reynolds

There has always been something slightly uncool about Radiohead. The characterless name, binding them to that undistinguished pre-Britpop era of semi-noisy guitarbands with equally blah names like The Catherine Wheel. The albatross of "Creep," the sort-of-great, sort-of-embarrassing song whose rousing anthemic-ness they've long since complicated. The superfluous "h" in Yorke's Christian name. "Cool" has never been Radiohead's thing, though. Leaving all that hipster credibility stuff to the Sonic Youths, Becks, and Stereolabs, Radiohead instead lay their wares out on the stall marked "importance." They hark back to an era when bands could presume the existence of an audience that took them seriously, and audiences in turn looked to bands to somehow explain them rather than merely entertain.

This self-seriousness--the earnestness of being important--is why critics continually reach back for the Pink Floyd comparison. (That, and the sheer magnitude of Radiohead's music and themes). It's not the tinsel and tack of Seventies pop culture that is unsalvageable from that period. It's the solemnity and sense of entitlement with which bands comported themselves as Artists--the concept albums, the gatefold symbolism. Everything about Radiohead---the trouble they take over track sequencing the albums to work as wholes, the lavish artwork and cryptic videos, the ten month sojourns in their recording studio in the English countryside---connects them to the pre-irony era when bands aimed to make major artistic statements. In the age of pop's tyrannical triviality, there's something almost heroic about this unfashionable striving towards the deep-and-meaningful.

Like a lot of people of the electronic persuasion, I was eventually seduced by the ear-ravishing sonic splendor and textured loveliness of OK Computer. I've still got only the faintest idea of what Radiohead are "about", or what any single Computer lyric describes. Luckily for me, it's sheer sound that Radiohead have plunged into full-tilt this time round. Kid A's opening tracks make a mockery of the impulse to interpret or identify. "Everything In Its Right Place" is full of eerily pulsating voice-riffs that recall Laurie Anderson's "O Superman" or Robert Wyatt's Rock Bottom--bleats of digital baby babble and smeared streaks of vocal tone-color that blend indistinguishably with the silvery synth-lines. A honeycomb of music-box chimes and glitchy electronix that sound like chirruping space-critters and robo-birds, "Kid A" could be a track by Mouse On Mars or Curd Duca; Thom Yorke's voice melts and extrudes like Dali-esque cheese whiz. After this jaw-dropping oddness, the relatively normal rock propulsion of "The National Anthem"---a grind-and-surge bass-riff, cymbal-splashy motorik drums---ought to disappoint. But the song is awesome, kosmik highway rock that splits the difference between Hawkwind's "Silver Machine" and Can's "Mother Sky," then throws a freeblowing bedlam of Art Ensemble of Chicago horns into the equation. All wincing and waning atmospherics, the out-of-body-experience ballad "How To Disappear Completely" calms the energy levels in preparation for "Treefingers", an ambient instrumental whose vapors and twinkling hazes make me think of a rain forest stirring and wiping the sleep from its eyes. Now you too can own your own miniature of Eternity.

Revealing fact: a high proportion of Radiohead websites provide fans with "guitar tabs" as well as song lyrics, so that the Jonny Greenwood worshippers can mimic his every last fret fingering and tone-bend. Something tells me there won't be too many chordings transcribed from Kid A, though. Saturated with effects and gaseous with sustain, the guitars* work like synthesizers rather than riff-machines: the sounds they generate resemble natural phenomena--dew settling, cloud-drift--more than powerchords or lead lines. Radiohead have gone so far into the studio-as-instrument aesthetic (with producer Nigel Godrich as "sixth" member), into overdubbing, signal processing, radical stereo separation, and other anti-naturalistic techniques, that they've effectively made a post-rock record.

That said, Kid A's "side two" (no such thing in the CD age of course, but "Treefingers" feels like the classic "weird one" at the end of the first side) is more conventionally songful and rocking. "Optimistic," for instance, is mined from the same lustrous gray seam of puritan Brit-rock as Echo & The Bunnymen's Heaven Up Here and U2's "Pride (In the Name of Love)". "Idioteque" does for the modern dance what PiL with "Death Disco" and Joy Division with "She's Lost Control" did at the turn of the Eighties. Call it bleak house or glum'n'bass: the track works through the tension between the heartless, inflexible machine-beat and Yorke's all-too-human warble (he sounds skin-less, a quivering amoeba of hypersensitivity).

Lyrically, I'm still not convinced that Yorke's opacities and crypticisms don't conceal hidden shallows, c..f. Michael Stipe. But as just another instrument in the band, as a texture--swoony, oozy, almost voluptuously forlorn--in the Radiohead sound, he dazzles. He moves through the strange architecture of these songs with a poise and grace comparable to his hero Scott Walker. Initially it seems peculiar that a singer/lyricist who obviously expects listeners to hang on his every word, should have such deliberately indistinct enunciation. But maybe that's just a ruse to make people listen very closely, in the process intensifying every other sound in the record, and the relationships between them. It works the other way: the music marshals and bestows the gravity that makes decoding the lyrics feel urgent and essential.

Yorke's words are less oblique this time round, but way more indecipherable; much of the time, we're in real Scuse Me While I Kiss this Guy territory. Where you can make them out, they evoke numb disassociation, dejection, ennui, indifference, isolation. "Optimistic" (it's not the least bit, of course) scans the world with a jaundiced eye and sees only bestial, un-evolved struggle: "vultures circling the dead", big fish eating little fish, and people who seem like they "just came out the swamp". "In Limbo" recalls the fatalistic castaways and ultra-passive nonentities from Eno's mid-Seventies solo albums. "Idioteque" bleats wearily about an "Ice Age coming" (presumably emotional rather than climatic) and "Motion Picture Soundtrack" closes the album with the proverbial whimper--a mushmouthed Yorke mumbling about dulling the pain with "red wine and sleeping pills... cheap sex and sad films" amidst near-kitsch cascades of harp and soaring angel-choir harmonies.

On first, stunned listen, Kid A seems like the sort of album typically followed--a few years later, and after chastening meetings between band and accountants--with the Back To Our Roots Record, the retreat to scaled-down simplicity. ("We realized that deep down, in our heart of hearts, our early sound was what we're really about"--you know the score). With further immersion (and this is an album that makes you want to curl up in foetal ball inside your headphones), the uncommercialism seems less blatant, the songfulness emerges from the strangeness. The track sequencing, immaculate and invincible in its aesthetic righteousness, gives the album the kind of shape and trajectory that lingers in your mind; it's a record people will want to play over and over in its entirety, without reprogramming micro-albums of their favorite songs. Smart, too, of Radiohead to resist the temptation to release a double, despite having more than enough material, and instead stick to a length that (at 50 minutes) is close to the classic vinyl elpee's duration.

Kid A does not strike me as the act of commercial suicide that some will castigate and others celebrate it as. That doesn't mean it's not hugely ambitious or adventurous (it may even be "important", whatever that could possibly mean in this day and age). But the audience amassed through The Bends and OK Computer is not suddenly going to wither away. Part of being into Radiohead is a willingness to take seriously the band's taking themselves (too) seriously. The initial alien-ation effect of Kid A will not deter their fans from persevering and discovering that it's their best and most beautiful album. as well as their bravest.

* um, well, ah, writing this i was unaware that in fact there's not much guitar on the record at all, so those synth-like guitar-tones i was hearing were in fact probably synths, or at least Ondes Martenot....

Kid A

director's cut, Spin, 2000

by Simon Reynolds

There has always been something slightly uncool about Radiohead. The characterless name, binding them to that undistinguished pre-Britpop era of semi-noisy guitarbands with equally blah names like The Catherine Wheel. The albatross of "Creep," the sort-of-great, sort-of-embarrassing song whose rousing anthemic-ness they've long since complicated. The superfluous "h" in Yorke's Christian name. "Cool" has never been Radiohead's thing, though. Leaving all that hipster credibility stuff to the Sonic Youths, Becks, and Stereolabs, Radiohead instead lay their wares out on the stall marked "importance." They hark back to an era when bands could presume the existence of an audience that took them seriously, and audiences in turn looked to bands to somehow explain them rather than merely entertain.

This self-seriousness--the earnestness of being important--is why critics continually reach back for the Pink Floyd comparison. (That, and the sheer magnitude of Radiohead's music and themes). It's not the tinsel and tack of Seventies pop culture that is unsalvageable from that period. It's the solemnity and sense of entitlement with which bands comported themselves as Artists--the concept albums, the gatefold symbolism. Everything about Radiohead---the trouble they take over track sequencing the albums to work as wholes, the lavish artwork and cryptic videos, the ten month sojourns in their recording studio in the English countryside---connects them to the pre-irony era when bands aimed to make major artistic statements. In the age of pop's tyrannical triviality, there's something almost heroic about this unfashionable striving towards the deep-and-meaningful.

Like a lot of people of the electronic persuasion, I was eventually seduced by the ear-ravishing sonic splendor and textured loveliness of OK Computer. I've still got only the faintest idea of what Radiohead are "about", or what any single Computer lyric describes. Luckily for me, it's sheer sound that Radiohead have plunged into full-tilt this time round. Kid A's opening tracks make a mockery of the impulse to interpret or identify. "Everything In Its Right Place" is full of eerily pulsating voice-riffs that recall Laurie Anderson's "O Superman" or Robert Wyatt's Rock Bottom--bleats of digital baby babble and smeared streaks of vocal tone-color that blend indistinguishably with the silvery synth-lines. A honeycomb of music-box chimes and glitchy electronix that sound like chirruping space-critters and robo-birds, "Kid A" could be a track by Mouse On Mars or Curd Duca; Thom Yorke's voice melts and extrudes like Dali-esque cheese whiz. After this jaw-dropping oddness, the relatively normal rock propulsion of "The National Anthem"---a grind-and-surge bass-riff, cymbal-splashy motorik drums---ought to disappoint. But the song is awesome, kosmik highway rock that splits the difference between Hawkwind's "Silver Machine" and Can's "Mother Sky," then throws a freeblowing bedlam of Art Ensemble of Chicago horns into the equation. All wincing and waning atmospherics, the out-of-body-experience ballad "How To Disappear Completely" calms the energy levels in preparation for "Treefingers", an ambient instrumental whose vapors and twinkling hazes make me think of a rain forest stirring and wiping the sleep from its eyes. Now you too can own your own miniature of Eternity.

Revealing fact: a high proportion of Radiohead websites provide fans with "guitar tabs" as well as song lyrics, so that the Jonny Greenwood worshippers can mimic his every last fret fingering and tone-bend. Something tells me there won't be too many chordings transcribed from Kid A, though. Saturated with effects and gaseous with sustain, the guitars* work like synthesizers rather than riff-machines: the sounds they generate resemble natural phenomena--dew settling, cloud-drift--more than powerchords or lead lines. Radiohead have gone so far into the studio-as-instrument aesthetic (with producer Nigel Godrich as "sixth" member), into overdubbing, signal processing, radical stereo separation, and other anti-naturalistic techniques, that they've effectively made a post-rock record.

That said, Kid A's "side two" (no such thing in the CD age of course, but "Treefingers" feels like the classic "weird one" at the end of the first side) is more conventionally songful and rocking. "Optimistic," for instance, is mined from the same lustrous gray seam of puritan Brit-rock as Echo & The Bunnymen's Heaven Up Here and U2's "Pride (In the Name of Love)". "Idioteque" does for the modern dance what PiL with "Death Disco" and Joy Division with "She's Lost Control" did at the turn of the Eighties. Call it bleak house or glum'n'bass: the track works through the tension between the heartless, inflexible machine-beat and Yorke's all-too-human warble (he sounds skin-less, a quivering amoeba of hypersensitivity).

Lyrically, I'm still not convinced that Yorke's opacities and crypticisms don't conceal hidden shallows, c..f. Michael Stipe. But as just another instrument in the band, as a texture--swoony, oozy, almost voluptuously forlorn--in the Radiohead sound, he dazzles. He moves through the strange architecture of these songs with a poise and grace comparable to his hero Scott Walker. Initially it seems peculiar that a singer/lyricist who obviously expects listeners to hang on his every word, should have such deliberately indistinct enunciation. But maybe that's just a ruse to make people listen very closely, in the process intensifying every other sound in the record, and the relationships between them. It works the other way: the music marshals and bestows the gravity that makes decoding the lyrics feel urgent and essential.

Yorke's words are less oblique this time round, but way more indecipherable; much of the time, we're in real Scuse Me While I Kiss this Guy territory. Where you can make them out, they evoke numb disassociation, dejection, ennui, indifference, isolation. "Optimistic" (it's not the least bit, of course) scans the world with a jaundiced eye and sees only bestial, un-evolved struggle: "vultures circling the dead", big fish eating little fish, and people who seem like they "just came out the swamp". "In Limbo" recalls the fatalistic castaways and ultra-passive nonentities from Eno's mid-Seventies solo albums. "Idioteque" bleats wearily about an "Ice Age coming" (presumably emotional rather than climatic) and "Motion Picture Soundtrack" closes the album with the proverbial whimper--a mushmouthed Yorke mumbling about dulling the pain with "red wine and sleeping pills... cheap sex and sad films" amidst near-kitsch cascades of harp and soaring angel-choir harmonies.

On first, stunned listen, Kid A seems like the sort of album typically followed--a few years later, and after chastening meetings between band and accountants--with the Back To Our Roots Record, the retreat to scaled-down simplicity. ("We realized that deep down, in our heart of hearts, our early sound was what we're really about"--you know the score). With further immersion (and this is an album that makes you want to curl up in foetal ball inside your headphones), the uncommercialism seems less blatant, the songfulness emerges from the strangeness. The track sequencing, immaculate and invincible in its aesthetic righteousness, gives the album the kind of shape and trajectory that lingers in your mind; it's a record people will want to play over and over in its entirety, without reprogramming micro-albums of their favorite songs. Smart, too, of Radiohead to resist the temptation to release a double, despite having more than enough material, and instead stick to a length that (at 50 minutes) is close to the classic vinyl elpee's duration.

Kid A does not strike me as the act of commercial suicide that some will castigate and others celebrate it as. That doesn't mean it's not hugely ambitious or adventurous (it may even be "important", whatever that could possibly mean in this day and age). But the audience amassed through The Bends and OK Computer is not suddenly going to wither away. Part of being into Radiohead is a willingness to take seriously the band's taking themselves (too) seriously. The initial alien-ation effect of Kid A will not deter their fans from persevering and discovering that it's their best and most beautiful album. as well as their bravest.

* um, well, ah, writing this i was unaware that in fact there's not much guitar on the record at all, so those synth-like guitar-tones i was hearing were in fact probably synths, or at least Ondes Martenot....

GANG GANG DANCE

Revival of the Shittest

(The Social Registry)

The Wire, 2004

by Simon Reynolds

Probably the most peculiar band to emerge from the ferment of out-rock activity in New York these past few years, Gang Gang Dance are a disconcerting live experience. Of the two shows I’ve caught, the first was fairly excruciating and the second was sublimely odd. Half the enjoyment, at least for over-acculturated hipster types, is trying to get a handle on where the band are coming from. You might momentarily flash on Can’s “Peking O”, The Sugarcubes’ “Birthday”, Attic Tapes-era Cabaret Voltaire, The Raincoats’ Odyshape, or forgotten downtown New York outfits from the Eighties like Saqqara Dogs and Hugo Largo, only to have the reference point confounded within 30 seconds as the group move back into untaggable territory. Gang Gang Dance’s music is like a myriad-faceted polyhedron. As it gyrates before your ears, different aspects flash into focus: No Wave, prog rock, drill’n’bass, psychedelia, glitch, assorted world musics, and more. But there’s always a feeling that the music is an entity, animated by some kind of primal intent, as opposed to being the byproduct of eclecticism and aesthetic flip-floppery.

Coming only a few months after their self-titled album on Fusetron, Revival of the Shittest is a vinyl rerelease of the group’s sort-of-debut, which originally came out in the autumn of 2003 in an edition of one hundred CDRs. Pulled together from live tapes, studio out-takes and rehearsals recorded on a boom-box, the six untitled tracks capture moments in the protean early life of the band. The first thing that grabs, or gouges, your ears is singer Liz Bougatsos. It’s hard (at least for someone with my limited grasp of technical terminology) to pinpoint precisely what she’s doing with her pipes--singing microtonal scales inspired by Middle Eastern music, perhaps? On Track 6, she emits what can only be described as a muezzin miaouw, while elsewhere there’s often a kind of 4th World/"Ethnological Forgery" aspect to both her vocals and the group’s music that suggests a sort of defective Dead Can Dance. Sometimes she seems to be simply singing every note as sharp as possible. Whatever the technique involved, the end result ain’t exactly pleasant--indeed, her ululations have a set-your-teeth-on-edge quality, like vinegar for the ears. But there is something queerly captivating about the way Bougatsos weaves around the strange, sidling groove created by her bandmates Brian DeGraw, Josh Diamon and Tim Dewitt.

Seemingly a blend of drum sticks on electronic pads, hand-percussion, and digital programming, Gang Gang Dance’s beats have clearly assimilated the bent rhythmic logic of electronic music in the post-jungle era. Heavily effected (often using reverb and delay), the drums generate a florid textural undergrowth redolent at various points of 4 Hero, Arthur Russell, and Ryuichi Sakomoto’s B-2 Unit. Needling guitars and glittering keyboards, often processed so that it’s hard to tell which is which, exacerbate the chromatic density. Writhing with garish detail, Track 5 feels like you’re plunging headfirst into a Mandelbrot whose patterns aren’t curvaceous but geometric--endlessly involuting cogs and spindles, the acid trip of a clock-maker surreptitiously dosed at work. On tracks like this, Gang Gang Dance music has a quality of deranged ornamentalism (think pagodas, mosques, but also coral reefs and jellyfish flotilla) pitched somewhere between exquisite and grotesque. A beautiful horror unfurls--folds and fronds, filigree and arabesque-that reminds me of Henri Michaux’s maniacally exact accounts of his mescalin experiences in Miserable Miracle.

At 31 minutes, Revival of the Shittest is just long enough--anymore and you’d be worn out by its polytendrilled density. At the same time, it’s this very quality of TOO MUCH-ness that makes Gang Gang Dance so compelling.

Revival of the Shittest

(The Social Registry)

The Wire, 2004

by Simon Reynolds

Probably the most peculiar band to emerge from the ferment of out-rock activity in New York these past few years, Gang Gang Dance are a disconcerting live experience. Of the two shows I’ve caught, the first was fairly excruciating and the second was sublimely odd. Half the enjoyment, at least for over-acculturated hipster types, is trying to get a handle on where the band are coming from. You might momentarily flash on Can’s “Peking O”, The Sugarcubes’ “Birthday”, Attic Tapes-era Cabaret Voltaire, The Raincoats’ Odyshape, or forgotten downtown New York outfits from the Eighties like Saqqara Dogs and Hugo Largo, only to have the reference point confounded within 30 seconds as the group move back into untaggable territory. Gang Gang Dance’s music is like a myriad-faceted polyhedron. As it gyrates before your ears, different aspects flash into focus: No Wave, prog rock, drill’n’bass, psychedelia, glitch, assorted world musics, and more. But there’s always a feeling that the music is an entity, animated by some kind of primal intent, as opposed to being the byproduct of eclecticism and aesthetic flip-floppery.

Coming only a few months after their self-titled album on Fusetron, Revival of the Shittest is a vinyl rerelease of the group’s sort-of-debut, which originally came out in the autumn of 2003 in an edition of one hundred CDRs. Pulled together from live tapes, studio out-takes and rehearsals recorded on a boom-box, the six untitled tracks capture moments in the protean early life of the band. The first thing that grabs, or gouges, your ears is singer Liz Bougatsos. It’s hard (at least for someone with my limited grasp of technical terminology) to pinpoint precisely what she’s doing with her pipes--singing microtonal scales inspired by Middle Eastern music, perhaps? On Track 6, she emits what can only be described as a muezzin miaouw, while elsewhere there’s often a kind of 4th World/"Ethnological Forgery" aspect to both her vocals and the group’s music that suggests a sort of defective Dead Can Dance. Sometimes she seems to be simply singing every note as sharp as possible. Whatever the technique involved, the end result ain’t exactly pleasant--indeed, her ululations have a set-your-teeth-on-edge quality, like vinegar for the ears. But there is something queerly captivating about the way Bougatsos weaves around the strange, sidling groove created by her bandmates Brian DeGraw, Josh Diamon and Tim Dewitt.

Seemingly a blend of drum sticks on electronic pads, hand-percussion, and digital programming, Gang Gang Dance’s beats have clearly assimilated the bent rhythmic logic of electronic music in the post-jungle era. Heavily effected (often using reverb and delay), the drums generate a florid textural undergrowth redolent at various points of 4 Hero, Arthur Russell, and Ryuichi Sakomoto’s B-2 Unit. Needling guitars and glittering keyboards, often processed so that it’s hard to tell which is which, exacerbate the chromatic density. Writhing with garish detail, Track 5 feels like you’re plunging headfirst into a Mandelbrot whose patterns aren’t curvaceous but geometric--endlessly involuting cogs and spindles, the acid trip of a clock-maker surreptitiously dosed at work. On tracks like this, Gang Gang Dance music has a quality of deranged ornamentalism (think pagodas, mosques, but also coral reefs and jellyfish flotilla) pitched somewhere between exquisite and grotesque. A beautiful horror unfurls--folds and fronds, filigree and arabesque-that reminds me of Henri Michaux’s maniacally exact accounts of his mescalin experiences in Miserable Miracle.

At 31 minutes, Revival of the Shittest is just long enough--anymore and you’d be worn out by its polytendrilled density. At the same time, it’s this very quality of TOO MUCH-ness that makes Gang Gang Dance so compelling.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

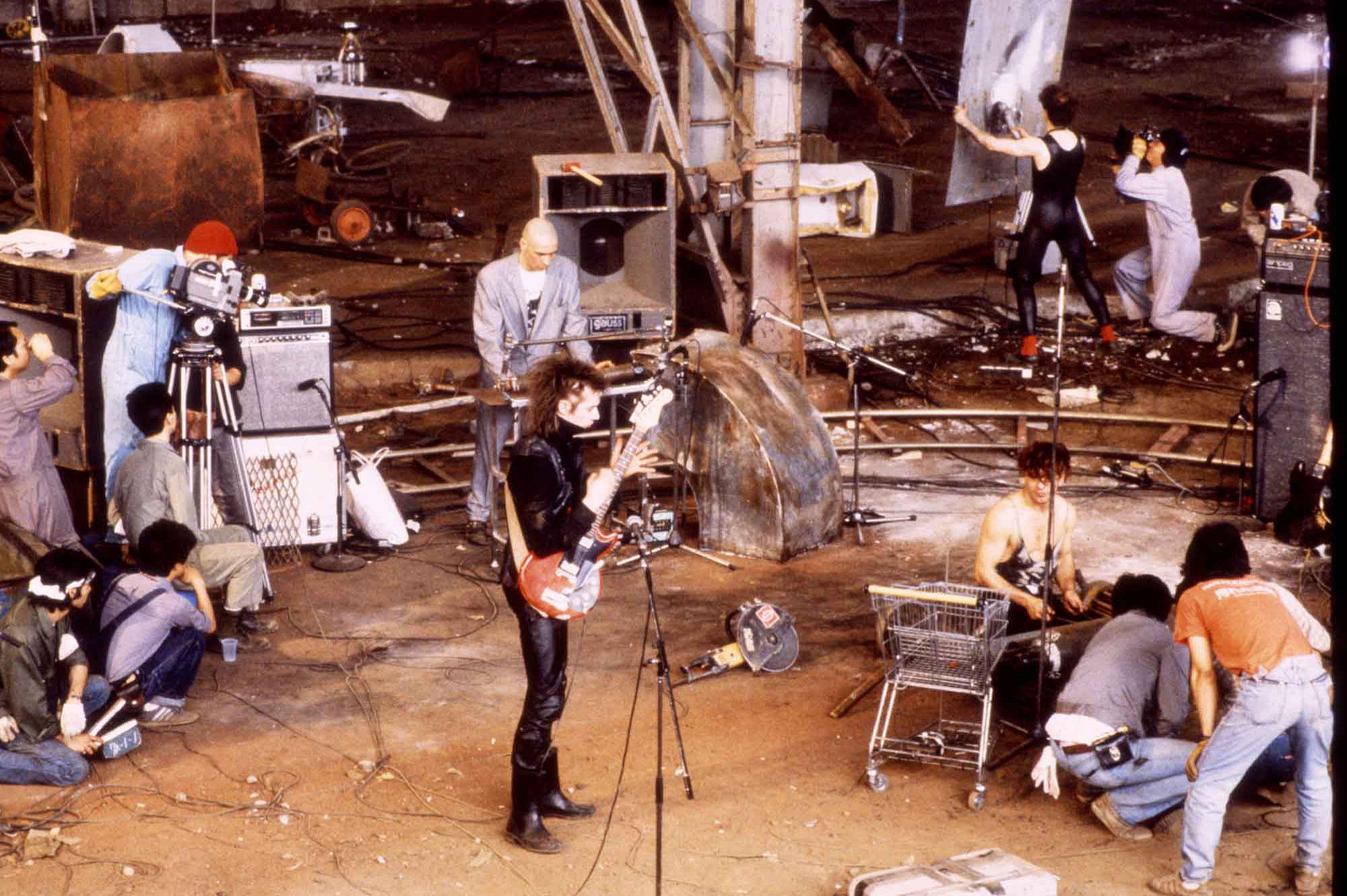

EINSTURZENDE NEUBAUTEN

Haus De Luege (Some Bizzare)

Melody Maker, 1989

By Simon Reynolds

After the conceptual perfection of their entry into the pop world, in which they announced the End (of music, of Western Civilisation), the logical step for Einsturzende might have been to disappear, or die. Instead, by carrying

on, they could easily be perceived as having settled into the ignominy of a career (and in the 'music business' no less). Certainly, in terms of the onward march of Rock Discourse they are nowhere now, just part of a rich (or threadbare,

depending on where you sit) tapestry of motley options: 'just music'. But in purely musical terms they're probably more interesting than ever, precisely because they've abandoned their early total gestures for more palatable formats.

And with the shift from out-and-out avant-gardism to the Blues and the Song, it's become possible to see that Einsturzende's "collapsing structures" have always been as much inside your own head as out there in the public realm of contestation. That the End of History they proclaimed was a private apocalypse: the demolition of the House of Lies (Haus Der Luege) that is the stable, self-policing self; the

deconstruction of the "BrainLego" out of which individual consciousness is formed.

Haus Der Luege starts with a "Prologue". It's an internal dialogue between two sides of the brain: the first devilishly advocates a poetry of impossible demands and self-immolatory desire, to which the Voice of Reason feebly counters "we could, but-". But before the case for vacillation and restraint can be recited, it's immediately drowned out by a sound like ten thousand vacuum cleaners

on the warpath. "Feurio" (Mediaeval German for fire) continues to expound the Bargeld manifesto of arsonist assault on the citadel of the self, for the massive

expenditure of unrecoupable energy. Sound-wise it's what Biba Kopf, in his excellent sleevenotes, calls a "musaic": a melange of hand-hit and synthetic sound, tier after tier of sonic rubble, mobilised into a rough-hewn dance shape at the mixing desk, in a manner that puts me in mind of PIL's "Flowers Of Romance".

"A Chair In Hell" is Bad Seedsy, with a "something wicked this way comes" beat tiptoeing up creaking stairs. "Haus Der Luege" is another excursion into disco concrete that dissolves into a waterfall of broken glass. Side Two starts with the nauseous hum of what are either flies or motorbikes, out of which drifts, like the Marie Celeste,"Fiat Lux". An immensely funereal item of ransacked, ghost

town blues, it's further proof of Bargeld's veneration for Sixties C&W visionary Lee Hazelwood. "Fiat Lux" fades into "Maifestspiele", where sounds of the annual May the First riots in Germany are draped in canopies of psalmic sorrow (is it a guitar? is it an orchestra? no, it's fourteen loops of Bargeld vocal played at different speeds). "BrainLego" is like Stone Age people trying to imitate Art Of Noise's

"Close To The Edit". "Schwindel" is urban Gamelan played on a bed frame, a choir of metallic chimes punctuated by the Bargeld Scream (a sound like a traction engine letting off steam). Finally, "Der Kuss", is an ode to the self- annihilating bliss of the kiss, constructed around deep register grand piano chords and a slide guitar solo like a coyote staring into the void.

To remind the listener of such a disparate array of styles and sound-sources (Lee Hazelwood's epic balladry, Gamelan metal-bashing, Penderecki's orchestral threnodies for Auschwitz and Hiroshima, Arvo Part's Mediaevalism, even Eskimo part-song) while at the same time impressing more firmly than ever the sense of an unshakeable musical

identity... well, it's a pretty cool manoeuvre for Neubauten to pull off. But all the while, Bargeld - ironically the consummate egotist - is lusting to breach his own identity, to "think myself to the end" ("BrainLego"), be consumed in a

self-ignited inferno of unreason.

SWANS

London University Union

Melody Maker, March 1st 1986

By Simon Reynolds

They took the stage looking a little like Grand Funk Railroad, but the Swans present a torture of sound as radical as Einsturzende Neubauten's. There are no melodies, no riffs even - bass and synthesizer are played percussively, combining with the drums as a single instrument.

The Swans songs consist of a single motif or sequence repeated with minimal variation, lurching forward at a punishingly slow pace. The guitar fills in the sound with surges and slashes of ugly noise. Michael Gira's voice is just another loop of abraded texture, an endless scar. And the Swans play very loud.

At times they're like agonized crawling things (some grim humour that they should adopt a name so symbolic of grace and dignity). At other times they sound like pop's abbatoir: only Glitter's "Rock 'N' Roll, Part Two" and the bleakest Killing Joke have approached a rock this merciless, this dehumanized, this dead. Perhaps Swans music exists at the point where the organic and inorganic meet, where the most degraded forms of life shade into the mechanicals.

Some bands use noise to blow the mind. The Swans music acts more like a compression of consciousness, a soul mangling. We were frozen in their noise, our minds unable to wander.

The only comparable experience I've had recently is the latest Cabaret Voltaire performances. Kirk and Mallinder used electronics of formidable opacity, percussively, to achieve a similar effect -- total sensory assault, an involuntary, joyless seizure of the attention.

For the Swans take rock beyond pleasure, beyond joy, to a realm where they can only be submission. What they find attractive in rock is not its liberating energy, its breaking free and emotional release. No, they have perceived in rock an urge to abasement, a repetition complex. This they've isolated and intensified, using the hypnotizing power of repetition, its compulsion, as a metaphor for the mechanisms of social bondage. They explore the sado-masochism at the roots of power psychology, by implicating us in a performance whose pleasure, whose hold, is essentially masochistic. Their music functions as both analogue and working example of the libidinisation of pain.

I don't know why the Swans want to take themselves, and us, so low. But I can't help but be impressed. Without particularly wanting to attend one of their concerts again.

FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD

Liverpool (ZTT)

Melody Maker, October 25th 1986

By Simon Reynolds

"Relax" was perhaps the least sexy record in pop history. What could be more coldly, hideously chaste than the "orgasm" near the end, that ludicrously amplified simulation of ejaculation?

No, "Relax" was driven by something far stronger than sensuality--by an idea of sex. Sex as threat, sex as shock, sex as subversion. Like striptease, "Relax" was all about fear.

Hence the bombast, the brazen exposure. Like "Love Missile" and "High Priest of Love", everything goes into flouting/flaunting, nothing is held back, and so there's no teasing intermittence, no intimacy. "Relax" didn't give us flesh or delight, it reveled in the Word, in saying the unsayable.

That pyrotechnic stretch from "Relax" through "Two Tribes" to "The Power of Love", from disobedience to schmaltz, still stands as one of the superlative pop essays, a glorious charade. The combined brilliance of Morley and Horn managed somehow to overcome the manifest fallibility of their human software -- for Frankie were sadly and severely unsexy, devoid of charisma or presence, so small next to the MUSIC and the GESTURES.

Back then, we could ignore all this in the fracas. But the Frankie assault was meant to be apocalyptic in its perfection. How could there be a Day After, let alone anything as ignominious as a follow-up? Without that sense of turmoil or Event, there is only a pained awareness that there is nothing intrinsically fascinating about Holly and the lads, nothing voluptuous about his voice.

But the orgy must pick up where it left off. Back in Frankie's perfumed boudoir, the air hangs heavy like a dulling wine. Listening to this record I don't think of Nietzche or Huysmans, de Sade or Blake, I think of… Cityboy, "A Total Eclipse of the Heart", Arcadia, "She Loves Like Diamond", Mott… ""Warriors of the Wasteland" is like Iron Maiden trampling their way through the backdrops and setpieces of Lexicon of Love, "Kill the Pain" is like yobs trying on Dollar's stage costumes and bursting them at the seams.

The production is verbose rather than vivacious, no expense spared in the process of cramming every space with thousands of fiddly frills or dollops of mellotronic goo. "Maximum Joy" is the only mildly exhilarating fake here, the only time the wedding cake edifice of sound doesn't sag under its own soggy weight. Stephen Lipson directs with all the restraint of Cecil B. de Mille, making choirs of massed angels dance about the mix. He's Horn's protégé, (an) adept at taking the most wafer-thin "songs" and hysterically exaggerating them.

Every second of this record crassly simulates orgasm or its afterglow. But there's two reasons why Liverpool fails as an aphrodisiacal proposition. First, its airy, trebley sound, where every beat seems veiled in dry ice, lacks bottom, and so can't interfere with your biology. Second, like all ZTT music, it's overlit. How can there be arousal under these brazen spotlights?

The lyrics are the ripest gibberish, dotted with words like "sun", "moon", "oceans", "hell", "heaven", "sailboats of ice on desert sands", presumably to evoke the grandeur of Frankie's vision. Frankie would convince us they're possessed by a barbarian insatiability: there seems to be some kind of quest for a nebulous glory, a pagan existence of perpetual joy, perpetual motion.

At one point a Scouse voice muses "in the coming Age of Automation… Man might be forced to confront himself with the true spiritual problems of living." Frankie's solution to this quandary appears to be a mystical investment in pleasure. Like Prince, they are saying "party up, before we all die". Unlike Prince, though, they make the pleasure principle seem incredibly boring.

Thursday, April 3, 2008

NEU!

Neu!

Neu! 2

Neu! 75

Spin, 2001

By Simon Reynolds

Neu! has got to be one of the most beautifully apt names to ever grace a band. The Dusseldorf duo's cruise control surge of steady-pulsing drums and quicksilver guitar creates the sensation of gently hurtling into a dazzling future--a world where everything is glistening and newborn. Forming Neu! in 1971 as a breakaway offshoot from Kraftwerk, drummer Klaus Dinger and guitarist Michael Rother pioneered the style that critics christened "motorik": a unique twist on the thread of white line fervor running through rock'n'roll, from Chuck Berry's "No Particular Place To Go" to Canned Heat's "On The Road Again" to The Modern Lovers's "Roadrunner". Neu!'s music tingled and throbbed with urgent anticipation, yet exuded a distinctly German serenity. Appropriately, the culture that had invented the autobahn also spawned, with Neu! and Kraftwerk, the most sublime sonic expressions of motion-as-state-of-grace. Now, after years of only being available as bootlegs, Neu!'s motorik trilogy gets an official CD reissue on Astralwerks.

"Hallogallo", the first track on the self-titled debut, is a wordless manifesto calling for fresh frontiers, new horizons, cultural renaissance. Ten minutes long, built from just Drummer's pounding drums and Michael Rother's iridescent overdubs (Neu! had no bassist and seldom used vocals), this is supremely transcendent and entrancing rock. Like the Velvet Underground a few years earlier and Television a few years after, Neu! sketched a blues-less blueprint for rock's future, and artists from Bowie/Eno to PiL, the Fall, and Stereolab picked up their glittering trail of clues. On "Hallogallo" and "Fur Immer" (the equally exhilarating and lengthy epic that kickstarts Neu! 2), Dinger & Rother's approach is minimal-is-maximal. What sounds initially like mesmerising monotony on closer listens is revealed as an endlessly absorbing tapestry of subtle shifts and intricate inflections. Dinger especially was the maestro of playing rhythmic accents around the basic four-to-the-floor beat while maintaining the feel of monolithic relentlessness.

Motorik wasn't the only card in Neu's hand, though. The grinding clangor and harshly chiming harmonics of the debut's "Negativland" flash-forwards to Sonic Youth's EVOL and Sister. "Lila Engel," from Neu! 2, is a neanderthal stomp that might, in some parallel universe, have displaced "Rock'n'Roll, Pt 2" as every sports fan's fave yell-along. And that album's entire second side consists of drastically accelerated and slowed-down versions of the single "Neuschnee" and its B-side "Super": a surprisingly entertaining and conceptually stimulating manoeuvre, albeit born of sheer desperation (Neu!'s recording budget ran out too soon!). Neu! 75, the duo's masterpiece, is also their most placid record, its first side gradually decelerating from the poignant, piano-cascading canter of "Isi" through the snowcapped majesty of "Seeland" to the beat-less seascape lull of "Leb' Wohl," all breathless blissed gasps and lapping surf. But really it's "Hallogallo", "Fur Immer," "Neuschnee," and the pedal-to-the-metal proto-punk roar of "Hero" (from Neu! 75) that represent Dinger & Rother's claim for a place in the rock canon. No band has ever surpassed these hymns to the glory of going-nowhere-fast.

NEU!

Neu!

Neu! 2

Neu! 75

Uncut, 2001

By Simon Reynolds

Don't wanna folderol about Neu!'s pervasive influence and ahead-of-their-timeness. Yeah, the roll call of debtors is long (Bowie cribbed notes for Low/Heroes, Stereolab's hocked up to their elbows, Spiritualized blah Sonic Youth yawn...), but these monumental records STAND ALONE in their astonishing beauty and soul-smiting might. Don't even wanna blather overmuch about Neu!'s innovativeness, 'cos that perpetuates Krautrock's image as sound-laboratory research, whereas this stuff was TORN from the heart-and-souls (muscles 'n' ligaments too: this is physical music) of Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger--a chalk/cheese, yin/yang duo who didn't get on except when making music together. Indeed, bad blood's the reason it's taken so long for these official re-issues of Neu!s oeuvre to materialise.

No guff today, then, just gush. Briefly members of Kraftwerk, guitarist Rother and drummer Dinger released their debut as Neu! in 1972. 10 minute opener "Hallogallo" is both blueprint for their "motorik" sound and a wordless cultural manifesto. Rother's talked about Neu! being inseparable from the late Sixties/early Seventies moment in Germany (student radicalism, anarcho-hippie communes, Red Army Faction, etc) and truly their music tingles with hope-against-hope idealism, yearnings for rebirth, breakthrough, new frontiers. With Dinger setting the beat on cruise-control for the heart of the sun, Rother overdubs a golden horde of guitars: gaseous with sustain, light-streaks of psychedelically-reversed tone-color, glistening flecked rhythm chords.... The result is the whitest music since the Velvets yet oddly close to the black aesthetic Amiri Baraka dubbed "changing same": the groove that just keeps on keepin' on, yet absorbs you with its endlessly shifting inflections and accents. Rest of the debut's less motorik, more avant-rock: "Sonderangebot" could be an alternative soundtrack to the alien obelisk scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey, while "Negativland" meshes clockwork bass-and-drum pulse-groove with howlround guitar-scree to create an unusually disturbed and menacing vibe for this usually rhapsodic group.

Neu! 2 basically reprises the debut's winning formula--at least until the budget ran out, and Rother and Dinger had to fill up Side Two with sped-up and slowed-down versions of a recent single! It opens with 11 minute epic "Fur Immer", whose driving Dinger-pulse seems to churn up a radiant slipstream of Rother-dust in its wake. More weirdshit follows: found sounds, eerie ambience, interrupted by the caveman stampede of "Lila Engel" (imagine "Rock'n'Roll, Part 2" meets "Sister Ray"). Then it's onto the 78 rpm and 16 rpm versions of "Neuschnee" and B-side "Super": not as irritating as you'd expect, highly listenable actually, and, sheer desperation aside, conceptually clever in John-Cage-meets-turntablism stylee.

The fissile Neu! separated for a few years, then reconvened for one last blast: their masterpiece, Neu! 75. Piano-and-synth instrumental "Isi" could be Krautrock's "Penny Lane", except it's wistful for the future rather than nostalgic. "Seeland" is like a first-class sunset, Rother's celestial pageant slowly unfurling over Dinger's ceremonial stealth. "Leb'Wohl" lowers your metabolism further still with its becalmed oceanside idyll, then "Hero" revs up again as its glorybound protagonist hurtles down the road-to-nowhere in a dazzling blare of chord-strum and wind-tunnel vocals. After Neu!'s final disintegration, Zen-scented Rother followed the "Seeland" path into a pretty but placid solo career, while velocity boy Dinger contined Neu!'s proto-punk speedfreak side with his terrific band La Dusseldorf. But it's with the holy Neu! trinity that Rother and Dinger etched their lofty perch in the rock pantheon. There's nothing "educational" or difficult about this music: Neu! should thrill anybody who's ever felt rock's rush.

These reissues dedicated to Klaus Dinger, sonic visionary and one of rock's greatest drummers. RIP.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)