Are you Sheffield born and bred?

“I was born in Sheffield [in 1953], but spent my

teens – this is late Sixties, early Seventies – in Nottingham. And then went to

Sheffield University, starting in 1973. Although

it was mainly engineers and had a good metallurgy department, it had a

substantial arts side to it too. And it was a fairly leftwing place. I studied philosophy.

I quickly got drawn into the student newspaper

Darts. I edited that during my second year. I did my finals in

1976.

“That year I applied in response to the

famous ‘hip young gunslingers’ advert that the New Musical Express ran,

when they were looking for a new writer [the one that Julie Burchill and Tony

Parsons came first equal for the staff writer job, so they gave jobs to both of them, and Paul Morley was runner-up]. During much of this time I worked part-time at

a branch of the Virgin record shop in Sheffield - a funky little store at the

bottom of this street The Moor. That was

pretty cool – the shop had this row of old airline seats and people would

listen to albums on “cans, man!” – headphones. People would sit and listen for

ages. We’d enjoy putting records on in the store. The shop had loads of

deletions and cut-outs, so it was a good grounding for listening and learning

about music.

“A thing to note about Sheffield then

is that it was a bit of equivalent to San Francisco. It’s always

had this leftist bohemia thing, in terms of attitudes. When Ornette Coleman

played the UK, he’d play London, and he’d play Sheffield – because he had a

constituency there, and people were prepared to go to the trouble of putting him on

there.”

What were the crucial

nodes of Sheffield bohemia?

“There was Rare & Racy, this store

in the university district, which was full of second hand books and second hand

records. Antiquarian books. It’s still there, and still a fantastic shop. The

guys that run it were a bunch of old jazzbos - very bohemian. Unlike most

bookstores where there’d be this hush, like in church, in Rare &

Racy there’d be this cacophonous racket

of free jazz, things like Sun Ra. Or John Cage. The Rare & Racy guys only

liked avantgarde jazz, contemporary European avant-garde, and old blues. So,

you’d hear Skip James or Charlie Patton wheezing away at you.

“And then another key node, a venue

for early electronic stuff was Meatwhistle – a sort of youth club and community

centre, a place behind the city hall. Human League, Adi Newton [Clock DVA] all

played there. A lot of people came out of that Meatwhistle mulch.

“Then there was Cabaret Voltaire, who

had their own thing going. Before the Cabs had a record out, they used to come

into Virgin. I had hair down to my waist

in those days. They came up to the counter and asked 'Have you got any records by Cabaret Voltaire?'.

I’d heard of the name, and what I’d heard about them sounded really intriguing

to me. So, I said ‘As far as I know they haven’t got anything out yet, but I’d

really be interested in hearing them, cos it’s my kind of thing.’ I remember

them being quite shocked that this guy who looked like a Ted Nugent fan was heavily

into that kind of that stuff. Ever since then we’ve been mates.

“Of the two big constituencies in

Sheffield as far as music goes in those days, one was metal / hard rock. Every metal band

would come to play the Sheffield City Hall. When ordering up albums for the

shop, 200 or 250 was a good order for an album - as an initial order that meant

the band was a big seller. The only groups that did that were Sabs, Quo or Zep.

"The other huge thing was glam. Not the Sweet or Gary Glitter, but Roxy Music and Bowie. They were a huge influence in Sheffield. It was this working-class thing of dressing up - but not just dressing up, being prepared to be outrageous and being into this weird music.”

"The other huge thing was glam. Not the Sweet or Gary Glitter, but Roxy Music and Bowie. They were a huge influence in Sheffield. It was this working-class thing of dressing up - but not just dressing up, being prepared to be outrageous and being into this weird music.”

So, Sheffield youth

were into the Eno side of Roxy as much as they were into the Ferry side?

“Definitely. It was the experimental

side of Roxy and glam that was interesting to most people. There was this club,

the Crazy Daisy – that was the place that had a big glam night. People would go

and dress up for it.

Roxette (1977) from NWfilmarchive on Vimeo.

Mal and Rich and Chris [Cabaret Voltaire - Stephen Mallinder, Richard H. Kirk, Chris Watson] and their gang were heavily into the sonics of Roxy. Although Mal was heavily into clothes too. He had two rooms in his flat, and one room was where he lived and the other was his wardrobe – and he had an ironing board in the middle of it. It was just completely full of clothes. Mal was the most stylish person I’d ever met; he always had a consummate sense of style.

Roxette (1977) from NWfilmarchive on Vimeo.

Mal and Rich and Chris [Cabaret Voltaire - Stephen Mallinder, Richard H. Kirk, Chris Watson] and their gang were heavily into the sonics of Roxy. Although Mal was heavily into clothes too. He had two rooms in his flat, and one room was where he lived and the other was his wardrobe – and he had an ironing board in the middle of it. It was just completely full of clothes. Mal was the most stylish person I’d ever met; he always had a consummate sense of style.

“The early Cabs gigs were trying to get

a reaction – it was a racket, just squealing noise. And there’d be films behind

them of god knows what: biological warfare experiments, people in chemical

warfare suits. They’d collect old Super-8 footage of things like that.

"Around 1975 or 1976, we became friends. They had been going since ‘73 or ’74. So, it was a bit after that I got to meet them. They had this studio in this old industrial building. The whole building was called Western Works – and they recorded in it and called the studio Western Works.”

What were they

like as people, Cabaret Voltaire?

“Richard’s always been a bit stroppy

–in that very Yorkshire way. He can be hellishly stubborn. That’s a typically

Yorkshire thing: ‘if you say don’t do

this, I’ll do it’. He’s got that thing

in his voice.

"In Sheffield it wasn’t like the London Musicians Collective where everyone’s got wire-rim glasses and that sort of avantgarde middle class attitude. In Sheffield, it was working class Dada. They were heavily into Dada and liked to get a reaction. Wake people up. Richard, then, mainly played guitar and clarinet. Mal did rudimentary bass and vocals, treated beyond legibility.

"In Sheffield it wasn’t like the London Musicians Collective where everyone’s got wire-rim glasses and that sort of avantgarde middle class attitude. In Sheffield, it was working class Dada. They were heavily into Dada and liked to get a reaction. Wake people up. Richard, then, mainly played guitar and clarinet. Mal did rudimentary bass and vocals, treated beyond legibility.

“Chris Watson is now quite famous. He

joined Tyne Tees as a sound engineer, and since then became one of the top

sound engineers in British TV. He does most of the David Attenborough things,

going around the world taping the sound of weird animals. And then solo he does

albums of strange ambiences of strange places. Chris was more straightforward

than the other two, at first glance. It was like a René Magritte thing, where you look like you work in a bank but you

do these weird art works. When you see Salvador Dali, from his appearance you

know what to expect from his paintings. Whereas looking normal is like

protective coloration. Chris looked more normal than Mal or Richard – and in

many ways, he was more normal. But he was very interested in sonic weirdness.”

Who else was

around in that moment just before and just after punk?

“There was the fanzine Gunrubber,

by one Ronny Clocks – a/k/a Paul Bower. He later went into local government in

London. And became a big figure in New Labour. Paul had always been very

political. Gunrubber was important.

"See, punk didn’t hit the same way in Sheffield as it did elsewhere. Punk in most other places in the UK inspired people to pick up a guitar and do the three-chord rock thing, in emulation of the Clash or the Pistols. But in Sheffield it didn’t happen that way, there were hardly any punk rock bands like that in Sheffield. Most bands wanted to make weird sounds. Early synths were prized. Or just boxes of tricks that people had made."

"See, punk didn’t hit the same way in Sheffield as it did elsewhere. Punk in most other places in the UK inspired people to pick up a guitar and do the three-chord rock thing, in emulation of the Clash or the Pistols. But in Sheffield it didn’t happen that way, there were hardly any punk rock bands like that in Sheffield. Most bands wanted to make weird sounds. Early synths were prized. Or just boxes of tricks that people had made."

So, there were no

Sheffield equivalent to provincial punk bands like Bristol’s The Cortinas, then?

“Well, there was 2.3, which was Paul

Bower’s band. They had a single on Fast Product. But even they weren’t very

punky. Paul was singer/guitarist in 2.3, but he was a scene maker as much as

anything.

“Another fanzine was Steve’s Paper.

That was Stephen Singleton, who formed Vice Versa – and which then turned into

ABC. Steve’s zine was more gossipy and concerned with scene-making. But he was

doing something at least.

“Another important node in the Sheffield

scene was this club Now Society aka Now Soc. That was within the university. These guys behind Now Soc felt that what the entertainments

committee were putting on was fucking rubbish – groups like Mud, or Osibisa. So,

they thought ‘there’s all these local bands, we should get them in here’. They set

up in one of the student bars in the university, funded through the student

union. Human League did their debut performance at Now Soc, which I reviewed

for NME. I always remember that gig because people had never seen a haircut

like that before – Phil Oakey had the asymmetrical haircut with the floppy

fringe that reached down to his chin on one side only. Phil had that look from

day one. The League were doing these comical kabuki moves in a self-deprecating

way. People were up for something new. Also, Kraftwerk were big in Sheffield,

people there loved them.

“Another important club was The

Limit. Def Leppard played there just before they broke. The Human League also.

They bought these Perspex screens, on HP [hire purchase], to shield them from beer

and gob thrown on them by the ‘what the fook’s this?’ people in the audience.

That was to protect the synths from shorting out with beer getting in the

works, which they couldn’t afford to happen.”

You did a special electronic feature for the NME, right? A five-page pull-out on "Synthesised Sound", January 5th 1980 - the first issue of the new decade!

You did a special electronic feature for the NME, right? A five-page pull-out on "Synthesised Sound", January 5th 1980 - the first issue of the new decade!

“Yeah. It seemed to me that there was basic

split between those who used synths to make weird sounds – people like Eno, or

Allen Ravenstine in Pere Ubu, or the Cabs – and then those who used the

keyboards to make pianistic and organ-like sounds, which would be all the prog

people like Rick Wakeman or Keith Emerson. But at that point I didn’t really

know about the psychedelic precursors who were doing more interesting stuffwith synths, like Lothar and the Hand People, Silver Apples, Fifty Foot Hose.

But I had been discovering weird electronic stuff since being a teenager in

Nottingham. We’d go to listen to obscure electronic albums on Nonesuch by

people like Morton Subotnick, in the record booths on a Saturday afternoon

right in the middle of this department store in Nottingham.”

Why do you think

there is this electronic connection with Sheffield in particular, and the

industrial North in general? There’s an attraction to the synthetic, and also a

feeling of affinity with groups like Kraftwerk, who are from the similarly

industrial Dusseldorf, or with American groups like Devo and Pere Ubu from

industrial Ohio.

“It’s one of those things, musique

concrete is a very industrial sound. In Sheffield you had these big steel

forges, and you’d drive past and hear the sound of hammers, these really big KLANGS.

That might have been influential on the Cabs – they recorded stuff that sounded

like that.”

Was Sheffield

starting to go into decline in the Seventies?

“In the Seventies, it still had a

strong industrial base. It’s always been known as the People’s Republic of South

Yorkshire. There was a deliberate decision by Thatcher to kill the city – because

it was so anti-Conservative. As soon as she got into power in 1979, every

program that would have helped Sheffield was denied to the city. And the city

just died. I went to live in London in 1980 and as I went back to Sheffield year

after year to visit, you could see it was just dying. In the Nineties it got a

bit of gentrification. But it was tragic what happened to Sheffield.

“In the Seventies, though, it did

still have this industrial base. People from outside of it thought of it as

this grim wasteland - huge steel rolling mills the size of several football

pitches, all this industrial grime. But to the people who worked in them, it

was their bread and butter.

“People were still employed. And the

dole culture was quite strong even then. If you were on the dole, you weren’t

ashamed of being on the dole. The dole was there to enable you to have time to

work on your music. So it wasn’t that everybody wanted jobs, everybody wanted

desperately to avoid having to work.

“But going back to Sheffield having this image of being an industrial wasteland…. Actually, Sheffield

is the most beautiful city in the UK. There was an act passed way back in the

last century concerning the development of Sheffield that stipulated that there

had to be substantial areas of greenery. Five minutes’ drive and you’re up in

the Peak District, and if you look down on the city from the moors, you can see

there’s huge parks dotting the city. If you go past Sheffield, on the M1, you

see the bad areas - the old industrial areas. But over on the west side of Sheffield

where the university was and where everybody I knew lived, it was beautiful.

All these beautiful old stone houses. And you’re in the countryside virtually. Sheffield

was called the Rome of Britain because it was built on seven hills, just like Rome

was built on seven hills.

Did you find the

journalistic clichés that you’d get in the early pieces on Cabaret Voltaire and

so forth – Sheffield as “grey” and “grim”– annoying, then?

“They did and they do annoy, a bit.

Because Sheffield is a beautiful place. Certainly compared to fucking Manchester,

which really is a grim and bleak place. For sure, there were areas of Sheffield

that were horrible – as there are in every town.”

Sheffield was also

famously left-wing. Labour always controlled the city council.

“It was hopeless for any other party

to try to get power there. The Lib Dems

have managed to share power now, thanks to what Blunkett did to the city when

he was head of the council, that whole farrago with the World Student Games,

which they fought tooth and nail to get, thinking it would be a big revenue

earner, but it bankrupted the city. So that led to a big swing against Labour.

But back in the old days, people were proud of having the cheapest buses in the

UK - 5p a ride, you could get anywhere in the city. You could get around easily on public

transport, which is just as well as being built on seven hills, it was hard for

cyclists. Some of the hills are pretty steep.

“In Sheffield, you could travel really

easily and cheaply. You could drink cheaply – beer was cheaper than down south.

People tended to walk around a lot. There weren’t that many people with cars.

It was mainly a pedestrian culture. If you were in a band, you would hire vans

to take the kit to the venue.”

And in Sheffield,

the kind of Labour was definitely Old Labour and to the left of the spectrum.

In favor of nationalization of the major industries. There were some unreconstructed

communists on the council, right?

“Oh yeah, a lot of Trots. A very

left-wing city and always had been. Nowadays it’s not, but nowhere is. But in those

days… There’s always been an undercurrent of a Communist Anarchist Trotskyite thing.”

Yet Sheffield

never really produced a militantly political postpunk group like The Pop Group

or Gang of Four… You didn’t get that kind of agit-prop band.

“The groups weren’t that left wing,

but the general populace was very left wing. Far more than any other British city

probably – maybe there’s places in Wales or Scotland could challenge it. The bands in Sheffield then weren’t political,

they were more anarchist. It’s that Yorkshire stubbornness – ‘no you’re not

going to organize me into this thing.’ That instinctive anarchism was a big

spur for a lot of the musical undercurrents in Sheffield during postpunk.

“And I may have had an effect on that.

Because you were more likely to get your band reviewed in NME if you

played that kind of music. As the paper’s Sheffield stringer, I favored certain

sounds. And occasionally groups threatened me because they were so annoyed I

wasn’t covering them. I may have contributed to that Sheffield postpunk image

in that sense.”

There was a period when the music papers would

discover and focus attention on a Northern city as a new hotbed of postpunk

action – first it was Manchester, and then Leeds, and then Sheffield, which the NME jestingly described as "This week's Leeds" - because it had become a syndrome by that point. Then after that Liverpool, and then they moved

on to Scotland. But what were the differences, and the relationships, between

Sheffield and Leeds and Manchester.

“In Sheffield, we always considered

Leeds a right-wing city. That’s despite Gang of Four and the Mekons coming from

there. Obviously, there was a left-wing undercurrent in Leeds, connected to the

university and polytechnic. But in Leeds, you had to watch out for the National

Front. There was no NF in Sheffield – not at all. Whereas Leeds was a very

strong centre for the National Front.

“As for Manchester, it just seemed fucking grim. I went there with the Cabs and this other group Graph, when they played the Factory in Hulme. One of them, after doing the soundcheck, went out to get some cigarettes – and got mugged.

“That would never happen in Sheffield. Sheffield 10 is the cool area – that’s the university district. I lived in Broomhill, which was John Betjeman’s favorite suburb in all Britain. But nobody got mugged, even if you went down the red-light district, in Havelock Square. It was still a safe place to go.”

Along with the

local Sheffield stuff, in NME you also used to write about groups like

Devo and Pere Ubu. Do you feel there was some kind of deep spiritual connection

between Sheffield and those industrial Ohio cities Cleveland and Akron?

“I sometimes wondered about that. When

The Modern Dance came out, I thought ‘this is the greatest album I’ve

ever heard’. It’s still my favorite of all time. It’s perfect, it has everything

for my taste buds -- the synths, the squealing noise, the attack, the moody

ruminations, and the bottle-smashing musique concrete elements. It has a drive

and vision that few other punk records have.

“Devo were the equivalent in their day

of Zappa in his day – Zappa in his prime. That early Zappa, Mothers of Invention stuff

was brilliant. Satirizing hippy culture even as it was being created, with We’re

Only in It for the Money. Very farsighted. Devo were doing the same thing for

the New Wave. Freedom of Choice is one of the great albums.

We know about The Human League and its offshoot Heaven 17, about Cabaret Voltaire, about Vice Versa becoming ABC, about Clock DVA… Who were some of the other notable after-punk outfits scrabbling around at that time in Sheffield?

“I’m So Hollow had one of the first

Wasp synths, with the touch sensitive keyboard. They were coming from the Wire

end of punk, which was big in Sheffield. Not the thrash aesthetic, but very

angular and considered. Later on, I’m So Hollow would have been considered

Goth, probably.

“Artery were an interesting band. They

used to wear aprons onstage. But they changed style so often it was hard to get

a fix on them. A curate’s egg - good in bits.

“There was also this group called Molodoy.

They had a poster that said ‘Right, right bratties - Molodoy’. That was Nadsat, the teenage slang from A

Clockwork Orange. Molodoy dressed up like Alex and his droogs from A

Clockwork Orange. Their music was like Wire – very angular and stern. There

was tension but no release, it was a very tightly repressed sound. Quite interesting

– but they never amounted to much.

Molodoy at the Limit Club, 1978

(pic by Garry Warburton)

“The Comsat Angels had so much

potential, but they were dogged by bad luck, bad choices, bad decisions. Musically they had lots of interesting ideas

and they should really have been like a U2 or an Echo and the Bunnymen. They

could have been a more interesting version of that kind of postpunk stadium

rock.

The Comsats were all set to tour America, supporting U2. But one of them fell ill. Robert Palmer was a big Comsats fan. Steve Fellows wrote all the Comsats songs, did the singing and guitars - and Robert Palmer invited him to work with him in the Bahamas. Steve used the money to pay off the Comsats’s debts.

Later Steve discovered and managed Gomez – they brought in a tape this record store in Broomhill, in Sheffield, where Steve was working part time."

The Comsats were all set to tour America, supporting U2. But one of them fell ill. Robert Palmer was a big Comsats fan. Steve Fellows wrote all the Comsats songs, did the singing and guitars - and Robert Palmer invited him to work with him in the Bahamas. Steve used the money to pay off the Comsats’s debts.

Later Steve discovered and managed Gomez – they brought in a tape this record store in Broomhill, in Sheffield, where Steve was working part time."

The Northern

cities might have had different vibes, musically, but they all shared a common antipathy

to London - a mixture of resentment of the centralized dominance of the capital,

and contempt for Southern effeteness.

“2.3 had a song that was anti-London [“I

Don’t Care About London”]. They did a parody of the Clash’s ‘London’s Burning”, and it went “’London’s

burning’ they all shout/but I wouldn’t even piss on it to put the fire out”.

That was pretty indicative of the Sheffield attitude to the nancies down South!”

But then you

moved down South in 1980…

“I felt I should get down to London

and impose myself on the NME. Stop being reticent. I’d been desperately trying to get them to accept

articles on Tuxedomoon and Chrome, groups I liked from San Francisco. It was a

bit of a struggle. I got a job on the staff.”

How did you find

it – London, and NME?

“I felt lonely. It was so much bigger

than anywhere else. I got on with the NME office people. The job was a

bit of a doddle, the editing. Cos I’d edited the fortnightly student newspaper

at Sheffield, I’d dealt with libel writs and all that – that was terrifying, receiving

a libel writ. So, working at NME was quite easy. But in Sheffield, it

being much smaller, you’d have people dropping in on their way home. But people

in London live ten miles away. So, you tended to do your socializing immediately

after work. It was easy to slip into that booze culture. There was a coterie of

us at NME who’d go drinking for long periods at lunch times – Ian Penman,

Monty Smith, Danny Baker, me. Got very drunk at lunch time and then wrote funny

shit in the afternoon. That was the best part of the NME.”

Writing for the

music papers in those days – especially NME but Sounds and Melody

Maker too – was much more powerful than being a music journalist later on.

Bands were influenced by writers… certain writers became cult figures, with

mystique and intrigue wafting around them… Did you get that kind of attention?

“Sometimes. But I don’t think I ever

had my photo appear in the NME. I thought that was a bad idea – because someone’s

going come up to at a gig complaining about something you wrote and you might get glassed. I wanted

to be anonymous.

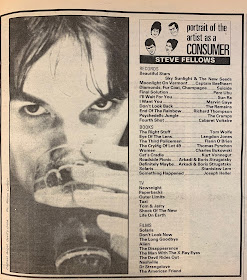

Andy's faves of 1981, in the NME Xmas issue that year

“The other thing is that people always

confused me with the other Andy Gill, the guy in Gang of Four. And he

gets it the other way round, people think he’s reviewing records for The

Independent. Even his dad thinks that! On tour, in America, apparently

someone once came up to him and asked “Are you the Andy Gill who writes for the

NME?”. Andy said “no”. And this guy goes, “oh…” – and just walked away! “

That whole late Seventies,

early Eighties period – it must have been an unbelievably exciting time to be

on the frontlines writing about it in real-time. It was incredibly exciting

just to read about it from a distance. Punk turning into postpunk turning into

New Pop…

“We used to have editorial meetings at

NME - they were ghastly affairs, arguments about genres and which things

should be covered and which things should be ignored. I would be thinking ‘we should just cover all

of this’. I could never understand

the factionalism, and the absolutist nature of the factionalism.”

So, you weren’t

involved in a faction at NME, then?

“Not really. To an extent, there was a cluster that was me, Ian, Chris Bohn, Paul Morley. But Morley was more a gadfly and had more of

a pop sensibility. It was Paul who once said that Stephen Mallinder was the

sexiest man in British pop. Which was ironic because at that time Morley looked

just like Mallinder!”

Talking about pop

sensibility, there was this huge shift from grim and bleak postpunk to bright

and bouncy ‘new pop’. And Vice Versa switched to become ABC.

“Vice Versa were an electronic band manqué - and it

was only when Martin Fry joined that they became this glossy pop thing. And

only when Trevor Horn got his mitts on them that they became this viable pop

thing. I remember thinking: ‘Blimey, ABC and Human League in the Top 10 - it

would never have happened in my day’. I

would not have bigged them up. I liked what the Human League did on Dare,

but I did think it was a dilute Kraftwerk.

Vice Versa live at Futurama festival , Leeds, 1980

“The day we left Sheffield to move

down to London, we did a moonlight flit to avoid paying the last lot of rent.

And I remember Ian Burden – then in this group Graph - coming round to the house. We had both been in

an improvising group called the Musical Janines, with Stephen Fellows and Mick Glaisher

and Kevin Bacon from the Comsats, just making a racket.

"Anyway, it was November or October 1980, I was about to leave Sheffield and Ian comes around and says “Have you heard, the Human League have split up?” Martyn Ware and Ian Craig-Marsh had left Phil Oakey and Adrian Wright in the lurch on the eve of this big European tour. And Ian says, “Phil has asked me to join the League.” Ian could play keyboards as well as bass, you see. Ian said, ‘I’ll have to learn all their repertoire, but that’ll only take about an afternoon, cos it’s all one-finger tunes.’ But he said ‘I’m not sure whether to do it or not’. And I was like, ‘for Christ’s sake, say ‘yes’. At the very least you’ll get to see Europe, and you might make a bit of money out of it, and it’s playing in a proper band’.

"Anyway, it was November or October 1980, I was about to leave Sheffield and Ian comes around and says “Have you heard, the Human League have split up?” Martyn Ware and Ian Craig-Marsh had left Phil Oakey and Adrian Wright in the lurch on the eve of this big European tour. And Ian says, “Phil has asked me to join the League.” Ian could play keyboards as well as bass, you see. Ian said, ‘I’ll have to learn all their repertoire, but that’ll only take about an afternoon, cos it’s all one-finger tunes.’ But he said ‘I’m not sure whether to do it or not’. And I was like, ‘for Christ’s sake, say ‘yes’. At the very least you’ll get to see Europe, and you might make a bit of money out of it, and it’s playing in a proper band’.

“So, Ian joined the Human League – and

of course, he co-wrote ‘The Sound of the Crowd’ and ‘Love Action’. Ian wrote the

riffs; Phil wrote the words. Later on, Steve

Fellows was living around Ian’s big house, so he was there when the post came

one day. Ian opens this envelope and there’s a royalty cheque for the European

earnings off just ‘Love Action’. And it’s a quarter of a million quid. And Ian

was like, ‘oh, more money….’ and he just left it on the table! Didn’t bank it

for weeks, because he’d just got so many of these checks. It’s a bit like the

Joe Cocker stories. Sheffield’s most

famous singer, but he had no head for money – and he had that typical working-class

self-deprecating thing. His dad supposedly found a load of checks in a drawer,

dating back to the early seventies. And his mum found a cheque for hundreds of

thousands of dollars in his jeans that she’d washed. Likewise, Ian, I think,

was a bit embarrassed by his success.”

So was Ian Burden

the musical genius of the second incarnation of the Human League?

“It was him and Jo Callis, who’d been

in the Rezillos. Jo and Ian were the ones who came up with the music. Phil was

the lyrics and a little bit of the music – and then the presentation, and the

overall vision. I have a lot of respect for Phil - he’s stayed true to his

ideals. And always he stayed in Sheffield. He found it a bit embarrassing,

being famous and recognized. He didn’t feel hip enough for London. Found it a

bit hard to mingle with the music industry."

What about ABC?

Did you care for them?

“Well, I came up with that phrase ‘the

Lexicon of Love’. That was the headline I gave this live review Penman did of

ABC. Ian and I still argue over who came up with it, actually. It was one of

their first gigs, more like a PA, because they couldn’t play. ABC was really a

Trevor Horn fantasy constructed in the studio.

“Did I care for ABC? Well, like one ‘cares’

for an extremely sweet candy. Stephen Singleton, back when he was doing Steve’s

Paper, the fanzine – he was always going about ‘I’ve found some great

shirts in a second hand store’. Or ‘I’ve found some nice gloves.’ It was a very

fashion-mag, glam-oriented approach – into the visual aesthetic of punk, rather

than the music. So, it didn’t surprise me that much, ABC, as an extension of

that.”

“Talking of glam becoming punk, the

great lost Sheffield group, who were quite important, was The Extras. I managed

them for a short while. The singer John Lake was a sort of actor-poet singer – so

the songs were a bit like someone busking ‘characters’ over tracks that the

others had laid down. They were too late for glam, too early for the New Romantic

- and out of step with punk. It was a highly design-conscious type of music - all

the elements of glam were there, with a little bit of punk edge musically. The

lyrics were very literary and poetic, plugged into that Burroughs, cut-up

thing, but also that Bukowski thing. The keyboard player Robin Markin looked like

Steve Harley; singer John looked like Bryan Ferry; the bassist Robin Allen,

known at the time as Robin Banks, looked like Dylan, a mop of curly hair. And

then they had this sax player Andy Quick, thin as a rake, who looked the

spitting image of Rowland S. Howard from the Birthday Party. Bizarrely Andy

departed for the antipodes at virtually the same time as Rowland S. Howard came

over to England. Andy was quite a funny

character - lovely, but he could flip

over and become borderline dangerous. He nutted a window once somewhere and got

all this glass in his forehead. Just having a sax in the group made it a Roxy

Music, Andy Mackay thing.

“The Extras were very big in Sheffield,

but the timing was just off. Two years earlier, or two years later, they could

have made it. But they were the ones where everybody in Sheffield expected ‘Oh,

they’re going to be famous soon’. They moved down to London, got a manager there,

but it all fell apart.”

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Over at Pantheon, a rapidly growing archive of Andy Gill's writing. Which can also be found in copious amounts at Rock's Back Pages.

The first thing I read by Andy - and cut out and kept - I had never heard of Faust or even Krautrock, so the idea that it was a revolution that had been betrayed was a double intrigue

NME, April 11, 1981

Here's a tribute to Andy at The Independent, where he worked for many years.

Andy Gill can be seen and heard talking in this doc Made in Sheffield